|

Volcano National Park, Big IslandVisited 14 and 15 January 2007(PC Users, Push F11 to see more of the picture area) |

|

|

The windward side of the Big Island (Hawaii) is a place lush and strange. Tourism has yet to homogenize the area. Dangerous fogs rise from huge cracks in the ground. The only road that goes anywhere (and it's a loop!) is called Highway 11 and it sports signs thanking its volunteer cleaners such as the Raëlists, a religion that believes that UFOs delivered genetic engineers to create intelligent life on earth. If so, their work is largely undone -- as is the very ground in this part of the world. The Big Island adds about 40 acres a year, thanks to the volcano stewing in these photos. Had the UFOs landed in the desolation depicted here, they'd probably be right at home. These moonscapes are of the Kilauea Caldera in Volcano National Park, HI. ( Can you say kee-loo-WAY-uh? If so, you know the Hawaiian word for spewing, but I wouldn't use it at parties.) |

|

|

Fueled by a molten rock (magma) pump 42 miles below, the 600-square-mile Kilauea is arguably the world's most active volcano. It's one of five "shield" volcanoes that formed the Big Island. When lava is very hot, it flows easily and forms shield volcanoes named because they look like an overturned shield. If you're not into warrior metaphors, think of them as wok volcanoes. Shield volcanoes have fairly gentle slopes with heights about 1/20 of their widths. These pictures show Kilauea's Summit Crater (about 4100 feet above sea level), a 2 by 3 mile depression formed by collapsing volcanic rock sanded by water and wind. Since the collapse (210-500 years ago), Kilauea has been filling up its crater with frequent eruptions since at least 1790. When the subterranean chamber is filled, with magma, the summit holds its mountain shape; but as eruptions empty out the magma, pockets form. Eventually the weight of the summit causes it to collapse back into the volcano. The depression in the first two pictures is the Halema'uma'u crater, (the word means place for bird; more on that in our supplementary picture page on the Caldera which you can reach by clicking here.) Halema'uma'u contained a lava lake that thrilled visitors such as Mark Twain. In 1924 it exploded, doubling its diameter to about 1/2 a mile. The top of the magma supply is about 2 miles below it and can erupt here or move laterally down the fissures along the southwest or (more likely) the east rift zones. |

|

Above we are looking across the Kilauea Summit Caldera (about 400' deep here) towards the Jaggar museum (that thin white line in the distance). Early (1800s) explorers noted the Caldera was 900' deep -- so lava has been filling up the basin since then. In some cases, this collapse causes deep rifts down to the magma levels miles below, allowing gasses to escape, including over 2000 tons of sulfur dioxide daily. These create the Sulfur Bank seen below near the Kilauea Caldera: |

|

For lots more pictures of the Sulfur Banks, click here. Volcano National Park has well marked hiking trails that take you around and into the Caldera. Here's what the Caldera looks like from the inside as seen along Bryan's trail: It's a little like walking in a very large black bathtub with a rain forest growing up the sides: |

|

Earthquakes frequently collapse the sides of the Caldera into such rock piles called talus. For lots more pictures from this beautiful hike through moonscape and rain-forest jungle, click here: Near the large (2 by 3 mile) Kilauea Summit Caldera lies a much smaller crater called Kilauea Iki (pictured below). (Iki means little in Hawaiian.) In 1959, over 1000 earthquakes were detected here within a 6 week period as magma began to bulge beneath Kilauea... |

|

|

...and then finally broke through the south wall moving 71 million cubic meters of lava through fissures such as the ones shown at left below. The eruption left a cone named Pu’u Pua`i which means "gushing hill." The vertical gouge was the base of lava fountains over 1100' high. Prevailing winds spread the ash and cinders from right to left, piling up to create this new hill. When the eruptions stopped, rock collapsed back into the vent, partially filling what was a 100' by 50' vent. |

|

The 1959 picture at left is courtesy of the USGS. The tiny glowing specs are burning trees. Many more pictures of this well-documented event are available by clicking here. The month-long eruption created a lava rapids that coated the crater with surreal rock tiling the still-active steam vent seen in the photo directly above this text. Seventeen episodes created a lava lake 400' deep. Almost 90% of the lava flowed back into the chambers through rifts. We arrived nearly fifty years later and the place was still smoking. |

|

To see more pictures of our hike down through the lush rain forest and into the barren steaming crater of Kilauea Iki, click here: Besides erupting at the summit, these shield volcanoes have riff zones, lines of lava that radiate from the top downward -- and in Kilauea's case, down to the windward shore. In fact, Kilauea has two rift zones, but its east zone is more active (and more spectacular as it steams into the Pacific). The USGS runs web cams in case you want to check out the action yourself by clicking here. To get from the volcano's summit to where the lava action is, visitors follow the Chain of Craters Drive down the east rift zone. The rift zone causes the volcano to grow laterally as magma creates tubes only 5-10 feet wide but a mile deep. Columns rise vertically from these deep tubes to the surface. Often the rock above these columns will collapse into these tubes, creating the pit craters through which the Chain of Craters Drive snakes. The photo below shows a typical pit crater: the 300' deep Pauahi crater. Made from remnants of three separate pit craters, Pauahi last erupted for one day in 1979. Many of the photos we took here are misted by the gasses and steam caused by seething Kilauea. |

|

|

We started down the Chain of Craters Drive in late afternoon, trying to time our descent so that we would see the lava flows just before and after sundown. (For pictures of that drive, including a few places where we weren't supposed to go, click here.) Cold afternoon rains kept chasing us from the craters back into our car as we wended our way to the sea 4000 feet below. Finally we arrived at the end of the road. From here, it's a two-mile+ hike over rough terrain to approach the eruption sites. |

|

Note the undulating curves above (the ones on the left in this photo above taken just past the end of the road leading down from Kilauea's summit to where lava flows into the Pacific.) This once smoothly flowing lava is called Pa-hoehoe in Hawaiian. Remember that old exurban myth about Eskimos having 32 words for snow? Hawaiians have at least two for lava. The flowing lava (seen in these next few pictures) is Pahoehoe. It's typically 3-6 feet thick. There's another more brittle looking, chopped up stuff called A'a (easier to spell than to say). It can be more than 30' thick. Chemically, they are the same -- it's all in how hot they flow. The hotter Pahoehoe flows more smoothly like micro-waved ice-cream topping. If it cools a bit, it can turn into a'a lava. In fact, the road had extended further before the fudge-flowing Pahoehoe decided to repave it. You wouldn't want Kilauea as your commissioner of public works: |

|

Pahoehoe is characterized by its ropy surface, much like a tablecloth pushed sideways. Here where the sidewalk ends and the land creates itself, the terrain is very rough. Since you have to look down anyway, you have every reason to admire the myriad forms sculpted by Pele, the Hawaiian's volcano goddess. Your admiration is somewhat tempered by the thought that you will be returning over this same lava in complete darkness save for whatever light you brought with you. |

|

We have lots more pictures like these posted; access them by clicking here. |

|

Volcanoes erupt (in this case flowing from fissures) along rifts that radiate out from their summits. Below is the Pu`u `O`o vent, where volcano Kilauea flows lava around the clock -- but like the moon in a sunlit sky, you can't see much of it until nighttime descends. So armed with flashlights and hiking shoes, we ventured past the ends of the earth (at least if you believe the National Park Service warning signs) to track it down. Pu`u `O`o has been making a nuisance of itself, gobbling up roads, villages, houses, visitor centers, and anything else on its fiery path since 1983, making it the longest-lived rift-zone eruption in 200 years. Besides boosting tourism in this economically depressed area of the Big Island, it will someday benefit the real-estate industry as it has already created more than 500 acres of beach real estate (so far) as it flows into the windward sea. |

Although Pu`u `O`o's once spit lava as much as 1500' into the air, it has since oozed out more predictably, creating a lava shield, a hill (sometimes a mountain) with successive layers of molten lava. Five shield volcanoes (two of them still active) created the Big Island of Hawaii which is more than twice the size of the other islands combined -- and, of course, is still growing. In fact, this rift zone extends not only from the 35 miles from the Summit to sea shore, but another 50 miles beyond deep into the ocean where the next Hawaiian island is forming.

The drawing (left) -- from one of the signs at the Jaggar Museum at Volcano National Park -- shows how these shield volcanoes arose from the ocean flow. Besides Kilauea (the low hill at about 6 o'clock position in this model), the other active volcano is Mauna Loa, about twenty miles from where these pictures were taken. Mauna Loa is the largest mountain by mass in the world, if you measure it from its base on the ocean floor. One of this island's three dormant volcanoes, Mauna Kea, is the tallest in the world at 33,474 feet (when measured from the ocean floor nearly 20,000 feet below).

Mauna Kea (shown at about 2 o'clock position) means "white mountain" since that high up, it snows, even in Hawaii. (Do Hawaiians have more words for lava than snow?) Mauna Loa also has snow -- but that snow can't be seen from the sea so fewer sailors knew it was there. Just like a person, as it ages (in this case about a million years), Mauna Kea is losing height as gravity relentlessly crushes its weight back into the ocean floor.

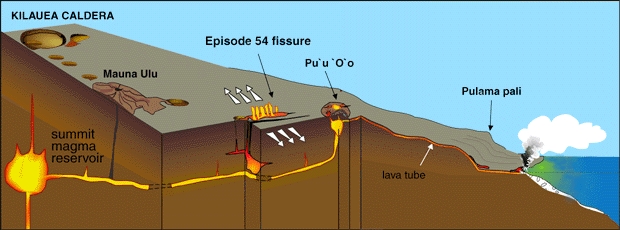

|

The US Geological Survey uses the picture at right to show the glowing fissure (pictured above) and the lava tubes flowing to the ocean that greats it with a steam bath (pictured below) about 7 miles away from Pu`u O`o. Both are fed from the magma (molten rock) reservoir below the Caldera at the summit, about 15 miles away. |

|

|

Above we see steam explosions as lava tubes create littoral (meaning beach) cones. Where 2,100°F (1,140°C) lava strikes the Pacific waters, all kinds of things can happen, most of them not beneficial to humans such as the creation of hydrochloric acid mist blowing inland, micro-wave sized rocks falling from the sky, and whole shoreline ridges collapsing into the sea. Fortunately, none of this happened to us as it wasn't our time to face the fire and brimstone. But if you want to see more sundown pictures we took in this area where lava meets sea, click here. Our hike ended after dark as we found ourselves scurrying over the rough Pahoehoe lava wearing headlamps. The next day we ventured back into Volcano National Park near the Caldera to walk through the Thurston Lava Tubes: |

|

Lava tubes are formed near the eruption point as the surface of the Pahoehoe lava cools, forming a roof over the molten flow. Hence an insulated tube forms. Eventually the lava breaks through downhill. When the eruption stops, the molten lava drains out, leaving the tube behind. The huge vent eruption that created the nearby Kilauea Iki crater created these tubes. The 400' long Thurston Lava Tubes are very popular at Volcano National Park as their entrance is only about 100 yards from touro-bus accessible parking lot. The approach and retreat is through a pit crater disguised as a beautiful rain forest nourished by over 100' of rain every year -- some of it on us. The first part of the tubes are well lit by electric lights. However, the back area is completely dark (very, very dark). Visitors are allowed in if they bring flashlights: |

|

See more Thurston (Nahuku) Lava Tubes pictures by clicking here. We next ventured away from Kilauea towards its much larger sister, Volcano Mauna Loa. (In fact, you could make the case that Kilauea really is a bump on the larger Mauna Loa). Our destination was the small park dedicated to the volcanic tree molds. These depressions (see below) are created when hot lava meets trees wet enough to resist burning until the lava cools. |

|

Near the tree molds is a delightful little bird park called Kipuka Puaulu. Along its 1.2 mile loop, we failed to see a single bird but did see some great vegetation. You can too: To see more pictures of the Bird Park and the Tree Molds (like the ones below), click here. |

In case you missed a link, here's how to get to the supplemental pictures:

If you'd like to see our pictures of the Haleakala Crater on Maui, click here. |

Especially at the higher elevations, this windward side of the Big Island never fails to delight with its bipolar scenery. Rapidly switching from bleak lava fields to incredibly lush rain forest, the landscape here is beautifully incredible and unpredictable. |

![]() This

work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.

This

work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.