Úbeda and its sister town,

nearby Baeza, are by far the two most Renaissance of

towns in Andalusia. For Úbeda, this happened when

a deep-pocketed noble named Francisco de los Cobos

accompanied his Emperor to Italy -- and brought back the

High Renaissance. He hired the best architect of his day

-- but ended up with the man’s apprentice, a young

stone mason named Andréa Vandelvira who would go

on to make Úbeda a town much copied in Spain and

the New World.

Úbeda has had some tough

times before and since: After being captured by King/Sain

Fernando III and the Christians in 1233, it was on the

firing line for 250 years until the Moors were driven

from Granada. During

that time, a 1368 war over the Spanish succession all but

leveled the town. Since then the 1755 Lisbon earthquake

(a Richter scale 9!) and the Spanish Civil War of the

1930s have further increased the havoc and

destruction.

Yet what’s left is a stone feast for the eyes;

over 48 buildings are still classified today as monuments

and UNESCO made the town a World Heritage site in 2003.

Plaza Vazquez de Molina

Perhaps the most magnificent Renaissance square in all

of Andalusia is Úbeda's Plaza Vazquez de Molina.

Once the old market square, it acquired its present set

of Renaissance buildings mostly in the 16th century when

the ministers of Spain’s new Emperor funded

Andalusia's most famous Renaissance architect to line

this area with palaces. Of the many beautiful buildings

that edge this square, four standout (clockwise from

upper left): Capilla del Salvador, Palacio de las

Cadenas, The Parador, and Iglesia de Santa Maria de los

Alcazares.

Palacio de las Cadenas -- the Palace of Chains

Úbeda is not only important in its own right, but

its architecture and city-planning inspired much other

building in Spain and in Latin America. Part of this was

due to Renaissance Andalusia's greatest architect,

Andréa Vandelvira, who left behind

his

legacy in stone here and through

his son’s writings. In a time of very little formal

training for architects, these influenced many builders

who followed. Above we look from the Palacio de las

Cadenas towards the Chapel of our Savior. Note that the

red car is parked on the street, not on the plaza. (More

on that later).

legacy in stone here and through

his son’s writings. In a time of very little formal

training for architects, these influenced many builders

who followed. Above we look from the Palacio de las

Cadenas towards the Chapel of our Savior. Note that the

red car is parked on the street, not on the plaza. (More

on that later).

Does the picture at right look familiar? We saw this

great Renaissance cathedral near Úbeda in its

provincial capital of Jaen. It’s the religious masterpiece of

Andréa Vandelvira. While Úbeda has no

church on this scale, Vandelvira’s secular architecture here is

spectacular. (If you want to see Vandelvira's

masterpiece in Jaen, click here.)

Back to Úbeda now where we see another three-story

façade with two "steeples" at either end: The

Palacio de las Cadenas (above and below). This is one of

Vandelvira's most important secular buildings. Its name

comes from its time as the jail when chains were

stretched across its entrance. It has also been used as a

Dominican nunnery and is now a triple threat as a pottery

museum, archive, and Úbeda's city hall.

Look carefully at the top floor where we see the

circular windows separated ...

... by 8 caryatids inspired (if

not done by) the French sculptor Esteban Jamet who was

active in Plateresque Spain around the time this was

built. Caryatids are usually female and a bit less

bellicose than what we see here (and not always as well

fed, either). The male warriors hold the coat of arms of

the family who first used this place as their palace --

the de los Cobos tribe who flourished in mid 16th

century. Inside the nearby chapel that we’ll soon

see, Jamet created many more caryatids as he brought this

classic Greek form into the High Renaissance that was

flowering in the soil of Gothic Spain.

... by 8 caryatids inspired (if

not done by) the French sculptor Esteban Jamet who was

active in Plateresque Spain around the time this was

built. Caryatids are usually female and a bit less

bellicose than what we see here (and not always as well

fed, either). The male warriors hold the coat of arms of

the family who first used this place as their palace --

the de los Cobos tribe who flourished in mid 16th

century. Inside the nearby chapel that we’ll soon

see, Jamet created many more caryatids as he brought this

classic Greek form into the High Renaissance that was

flowering in the soil of Gothic Spain.

Below is one of the turrets/viewing galleries that

straddle each end atop the Palace. This is a hexagon, a

common shape in this Renaissance town. Unlike most of the

rest of the facade, these Dorian pillars and the crowning

sculptures could use some restoration.

Besides being known as the palace

of chains (Cadenas), it's also called Palacio de Juan

Vázquez de Molina after the noble who paid

Vandelvira's bills. He was a member of the town's own

dynasty: the los Cobos family. More famous was his uncle,

Don Francisco de los Cobos, who served

as secretary of state for the Holy Roman Emperor Charles

V who is often considered to be the first king of Spain

(and a whole lot more territory besides). It’s

likely that Francisco de los Cobos was the 2nd most

powerful man in a Spain that had just expelled the Moors

and was creating the world’s most powerful empire.

Nephew Vázquez de Molina followed in his uncle's

footsteps and became Charles's secretary as well as that

of Charles' successor, Philip II. When these two ruled,

Spain was hands down

the world power. But this new country spent more

than it took in, and financial deficits eventually

contributed to Spain's downfall. (Aren't you glad that

can't happen today!)

Besides being known as the palace

of chains (Cadenas), it's also called Palacio de Juan

Vázquez de Molina after the noble who paid

Vandelvira's bills. He was a member of the town's own

dynasty: the los Cobos family. More famous was his uncle,

Don Francisco de los Cobos, who served

as secretary of state for the Holy Roman Emperor Charles

V who is often considered to be the first king of Spain

(and a whole lot more territory besides). It’s

likely that Francisco de los Cobos was the 2nd most

powerful man in a Spain that had just expelled the Moors

and was creating the world’s most powerful empire.

Nephew Vázquez de Molina followed in his uncle's

footsteps and became Charles's secretary as well as that

of Charles' successor, Philip II. When these two ruled,

Spain was hands down

the world power. But this new country spent more

than it took in, and financial deficits eventually

contributed to Spain's downfall. (Aren't you glad that

can't happen today!)

At right is another close-up of the 2nd and 3rd

stories -- actually not. These are the upper floors of

the palace of Charles V at the Alhambra in Granada.

Obviously Charles first secretary borrowed some ideas

from his Emperor. Above is probably the first Renaissance

building in Spain and precedes the Úbeda palacio

by 3 decades. It's the work of Pedro Machuca who probably

studied under Michelangelo. Vandelvira's influences are

easy to trace in stone.

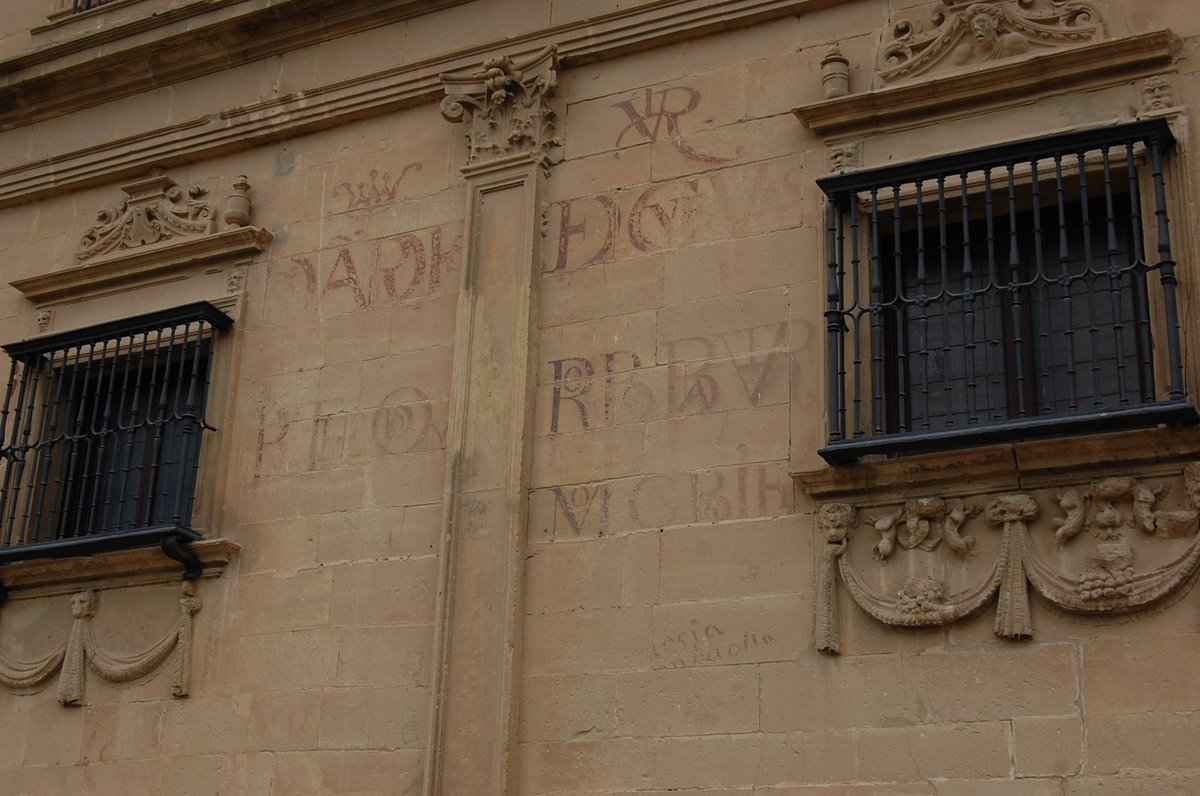

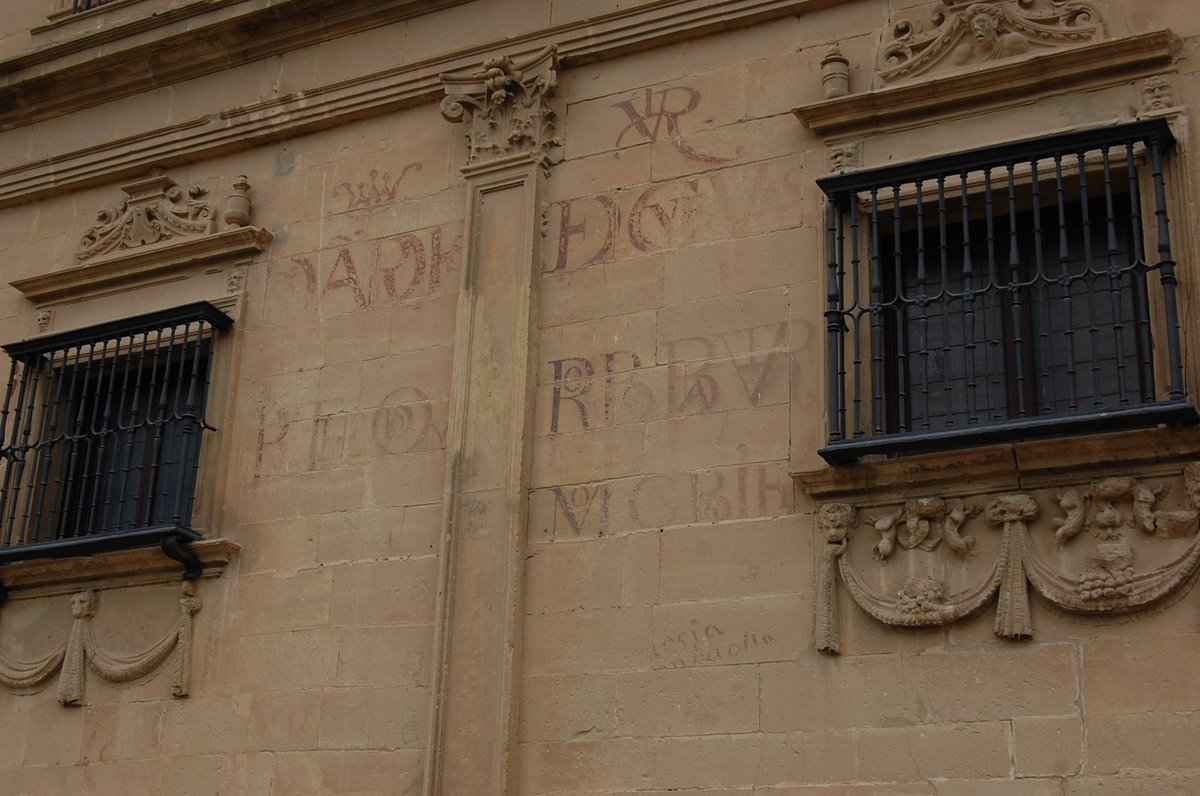

Below is a shot of the graffiti found on many of the

Renaissance buildings in Andalusian Spain. It's obviously

historic, but what does it mean? Vázquez de Molina

and Vandelvira built this palace in 6 years starting in

1562. Unfortunately, de Molina had no children and so he

decided to found a religious order to take over the

place. He undoubtedly had help from his brother who was

bishop.

Fernando Ortega Salido Palace -- the Parador

The picture below looks

east from the palace across the

long rectangle that is the Plaza Vázquez de

Molina. To the left is Úbeda's old prison (right

on the street with the nobles' palaces!) In the

foreground is a Renaissance fountain. To the left center

we see our next building, the Parador hotel. In the

background is the Capilla (Chapel) of Our Savior.

Below we look the opposite way

from the prior picture. Down the long Plaza

Vázquez de Molina is the more austere Deán

Fernando Ortega Salido Palace, another Renaissance work

of Andrés de Vandelvira. This was one of the first

Parador hotels, and was the first Parador that Dick

stayed in shortly after the global and personal darkness

of 9-11. On this trip we again used this for our

Úbeda base, looking out at this magnificent square

from the 2nd window from the left on the upper floor.

Below we look the opposite way

from the prior picture. Down the long Plaza

Vázquez de Molina is the more austere Deán

Fernando Ortega Salido Palace, another Renaissance work

of Andrés de Vandelvira. This was one of the first

Parador hotels, and was the first Parador that Dick

stayed in shortly after the global and personal darkness

of 9-11. On this trip we again used this for our

Úbeda base, looking out at this magnificent square

from the 2nd window from the left on the upper floor.

We probably had better plumbing than did the builder of

this palace: Don Fernando Ortega Salido, Dean of the

Cathedral of Malaga who, like the de los Cobos, was a

part of the Emperor's retinue. Note the lack of cars

here; no parking (other than luggage handling) is allowed

in the entire plaza. More places should do this,

especially if they look as good as Úbeda's public

squares. (On the down side, we found a few dents on our

rental car the next morning as we had to park it on the

street.)

During our stay, the Parador seemed empty, especially

around dinnertime when no more than three couples would

be in the dining room. The inner courtyard was

spectacular -- and typical of Vandelvira's palace

architecture.

Let's continue our tour of the Plaza Vázquez de

Molina with the town's most spectacular building, inside

and out, the building told everyone that young

Andréa Vandelvira was to be Andalusia's Frank

Lloyd Wright: the Chapel of the Savior (Capilla del

Salvador). Join us by clicking

here.

Please join us in the following slide show to

give Úbeda the viewing it deserves by clicking here.

|

|

|

|

Geek and Legal Stuff

Please allow JavaScript to enable word

definitions.

This page has been tested in Internet

Explorer 7.0 and Firefox 3.0.

Created on 15 February 2009

|

|

TIP:

DoubleClick on any word to see its definition.

Warning: you may need to enable javascript or allow

blocked content (for this page only).

TIP:

Click on any picture to see it full size. PC

users, push F11 to see it even larger.

<

legacy in stone here and through

his son’s writings. In a time of very little formal

training for architects, these influenced many builders

who followed. Above we look from the Palacio de las

Cadenas towards the Chapel of our Savior. Note that the

red car is parked on the street, not on the plaza. (More

on that later).

legacy in stone here and through

his son’s writings. In a time of very little formal

training for architects, these influenced many builders

who followed. Above we look from the Palacio de las

Cadenas towards the Chapel of our Savior. Note that the

red car is parked on the street, not on the plaza. (More

on that later).

... by 8 caryatids inspired (if

not done by) the French sculptor Esteban Jamet who was

active in Plateresque Spain around the time this was

built. Caryatids are usually female and a bit less

bellicose than what we see here (and not always as well

fed, either). The male warriors hold the coat of arms of

the family who first used this place as their palace --

the de los Cobos tribe who flourished in mid 16th

century. Inside the nearby chapel that we’ll soon

see, Jamet created many more caryatids as he brought this

classic Greek form into the High Renaissance that was

flowering in the soil of Gothic Spain.

... by 8 caryatids inspired (if

not done by) the French sculptor Esteban Jamet who was

active in Plateresque Spain around the time this was

built. Caryatids are usually female and a bit less

bellicose than what we see here (and not always as well

fed, either). The male warriors hold the coat of arms of

the family who first used this place as their palace --

the de los Cobos tribe who flourished in mid 16th

century. Inside the nearby chapel that we’ll soon

see, Jamet created many more caryatids as he brought this

classic Greek form into the High Renaissance that was

flowering in the soil of Gothic Spain.