During Roman times, this gate led across the river into a network of roads leading to the Via Augusta, Rome’s paved artery flowing through Andalusia from Cádiz on the Atlantic to the Pyrenees. This road ran 1500 miles and connected into Rome's massive system. The Romans built 50,000 miles of roadway primarily for military purposes. (Under the leadership of their great military hero, those upstart Americans built their Interstate Highway System in the last half of the 20th century; today they drive 1/3 of their total miles on its 45,000 miles.)

Whereas most Roman roads ran straight, regardless of terrain, in Spain, steep topography dictated that they lined the edges of the Iberian Peninsula with feeder roads onto the plains. As Córdoba was the capital of Rome's Baetica region, this was the most important entrance in the land that would become the Moors' Andalusia.

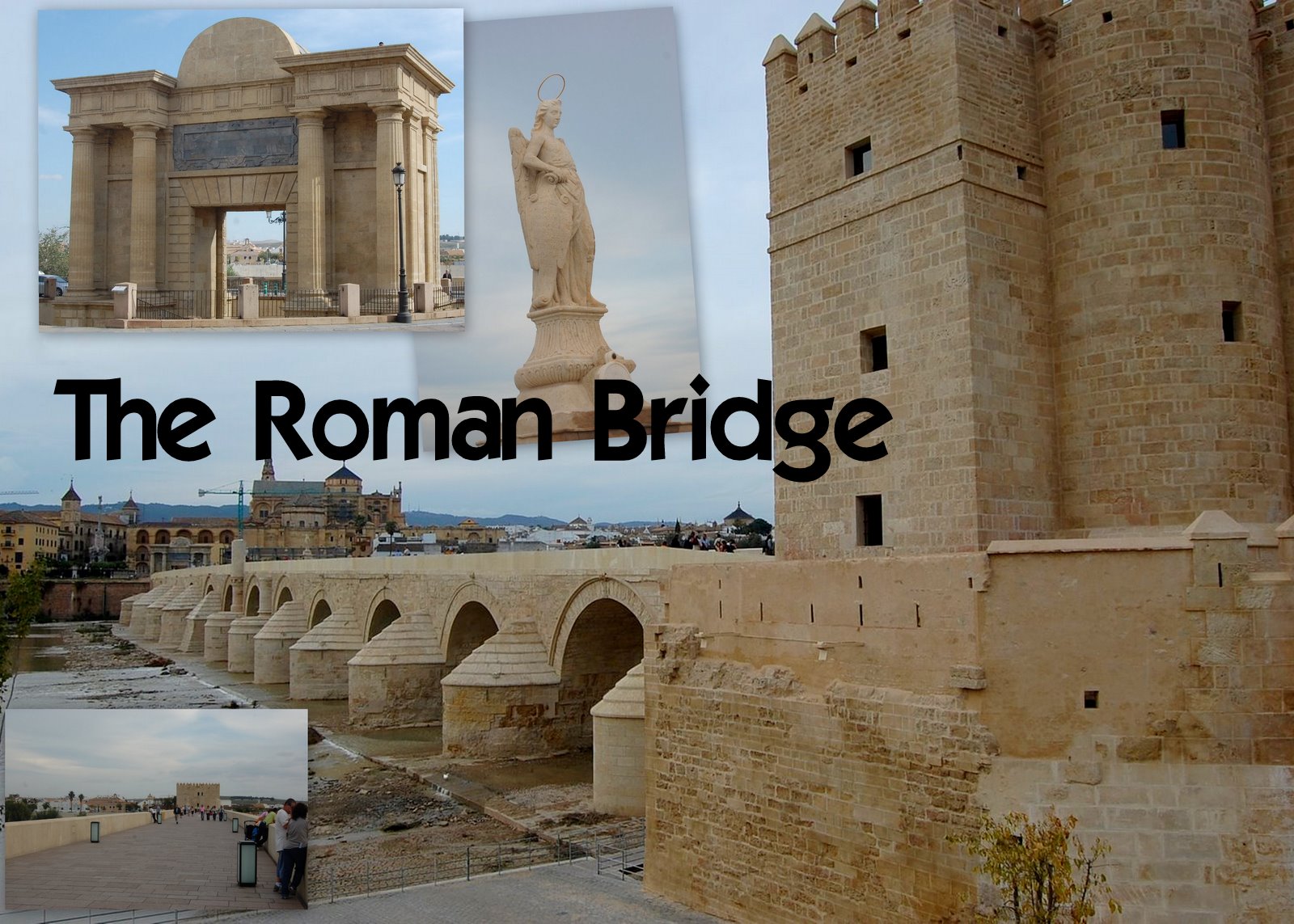

The ceremonial arch stands at the north end of the Roman Bridge which would be center bottom of this picture.The road then ushers visitors past the mosque and into the old Arab quarter to the north. Around 1912, the structures on either side of the arch were removed to make this freestanding -- becoming Córdoba's Arc de Triomphe. Over the centuries, the ground around it rose and so the base was excavated to return the gate to its original height.

Because it starts below the current street level, the arch seems a bit squat in the above view looking south across the Guadalquivir. Yet it is an elegant renaissance structure designed by Hernán Ruiz III (the Renaissance/mannerist grandson of the famous Córdoban architect family). He took over after a poor start, came in at triple the budget, and finished this set of Doric columns in 1576. In 2005 a major rehab left the bridge, its ceremonial gateway, and the defensive tower with a fresh-scrubbed look.

Facing the river (and showing itself to those who would be entering Córdoba by what until recently was its only bridge) is this crest flanked by two warriors. Philip II visited and inaugurated this gateway. At the time, Spain was the greatest power in the world.

This view shows how far below street level the base of the arch is. The arches seen here are at the southern end of the mosque. Cordoba’s walled defensive system had 13 gates; only 3 remain today.

This bridge has allowed only pedestrian traffic since 2004; for two millennia before that, it was the only way to cross the Rio Guadalquivir at Córdoba until a second bridge opened in the early 1950s. Its current scrubbed look can be attributed to a two-year refurbishment ending in January 2008, months before our visit. Built in the first century CE, it most likely replaced a wooden bridge in the same location. We look here south towards a medieval defensive tower called Torre de la Calahorra

The remains of several mills (Molinos) rise from the Guadalquivir and are easily seen from the Roman Bridge. A water wheel, which brought water from the river into the Mosque area through a short aqueduct, was dismantled when Queen Isabel complained that its racket disturbed her sleep. Beyond, new Córdoba rises on the far bank. Many of these building cranes have likely since disappeared as the unemployment levels in Spain exceeded 17% six months after this picture was taken.

Before steel, bridge building was essentially stacking stone leaning into one another, requiring wide rivers to be crossed by many arches. Originally 17 arches crossed the river here with about a total 360-yard span. Today there are only 16. Only 2 arches near the southern end are original. Many were rebuilt going back to the Moors' days.

The southern end of the Roman Bridge is anchored by several defensive towers that have been combined into one. They are collectively known as Torre de la Calahorra and were built by the Moors on the site of an old watchtower in the 12th century. Henry II (better known as Enrique de Trastámara) joined the two free-standing square towers with the cylinder in order to stave off his brother, King Pedro, as they fought over who would succeed to the throne of Castile.

The illegitimate son of Alfonso XI (Henry) won and ruled until 1379, fighting the Hundred Years War most of that time. Henry had much company as his father had 9 other illegitimate children with Henry’s mother. His half brother Pedro whom Henry both deposed and beheaded, was subsequently poorly treated by the history that Henry’s winning side wrote.

The moat has also been restored into a condition far more pristine than any true medieval ditch.

Henry’s victory over Peter presaged the darker side of medieval Spanish history. Henry enflamed the population against Peter through a deliberate anti-Semite campaign, calling Pedro the “king of the Jews.” (Heard that before?) Henry bested Pedro because the aristocracy supported him – and for three more centuries the nobles would be their own force against the monarchy. Not until Ferdinand and Isabel’s grandson Charles finally subdued the nobility would the monarchy become Spain's only significant central force.

But this circles returns ugly: The interactive museum inside this structure is sponsored by Fundación Roger Garaudy, named after the exiled French communist (now a Córdoba resident) who denies the Holocaust and claims that the US government sponsored the September 11 attacks. Hardly the name for a museum honoring Muslims, Jews, and Christians! Does Garaudy channel Henry II beside the Guadalquivir?

Above, the Guadalquivir looks none too navigable on this western side of the Roman bridge. Probably the Carthaginians started this town because the river let them trade this far inland. Trade continued into the middle ages. Once the New World was discovered, Seville, far downriver, became the dominant port.

The river looks low in this September picture, but has often inundated parts of Cordoba until the implementation of flood control technology in recent times.

Not the longest, but perhaps the greatest Spanish river (it name means "great river" in Arabic), the Guadalquivir was navigable in Roman days as far as Córdoba. (Today commerce stops at Seville.) Its 408 miles of stream fall nearly a mile in height and its waters irrigate much of the rich agriculture of Andalusia downstream from here.

The Mosque (distant right in the above picture) and the Roman bridge are located at a wide bend which thrusts the river northward on its western trek to the Gulf of Cádiz on the Atlantic. The building cranes in the old city are part of rehabilitation efforts, but these may come to an end soon as Spain's public sector debt is 50% of its GDP. Can you say "Socialist"?

|

Please join us in the following slide show to give Córdoba the viewing it deserves by clicking here. |

|

Geek and Legal StuffPlease allow JavaScript to enable word definitions. This page has been tested in Internet Explorer 8.0, Firefox 3.0, and Google Chrome 1.0. Created on June 15, 2009 |

|