Let's now explore the proud remains of Málaga

's long Moorish past: the restored Alcazaba and its

uphill partner, the Gibralfaro Castle which is pretty

much in its original condition. The fort itself (see

above picture) appears to be a long curtain wall

frequently interrupted by square towers of various

heights. In fact, it's a double wall with towers spiking

up from both inner and outer walls.

The curtain wall flows downhill making this resemble a

brick dragon sleeping on a hill or perhaps a disheveled

landscape by Georges Braque (a buddy of native

Malagueño Picasso.) The square towers suggest that

these were early fortifications. Eventually towers became

rounded so that battering rams would not have corners to

pulverize. Then attack artillery made both round and

square obsolete - and that happened here in Málaga

almost earlier than anywhere else.

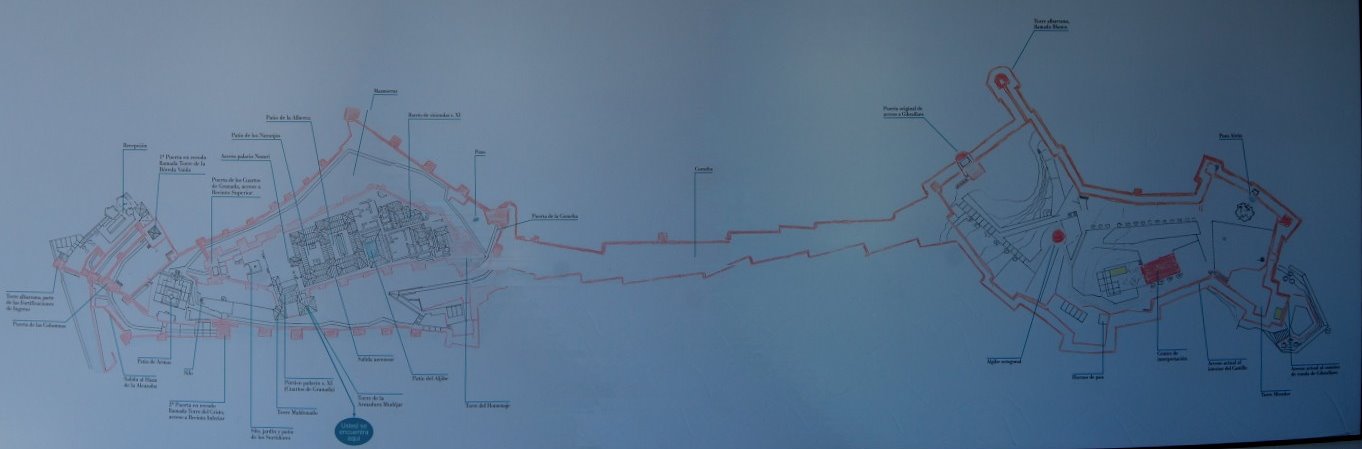

Topology dictates layout

This is the most misshapen fort you could imagine due to

the constraints of the steep terrain. At left is the

Alcazaba, the old fort built at the base of the hill with

the old city enfolding around it. Its problem was that

there was a higher hill to the east (right.) With the

invention of artillery, cannons could be dragged to the

top where they could send their cannonballs into the

Alcazaba. Therefore the Moors (in this case the Nasrid

ruler Yusef I) built a second fort on the higher hill

(the "Gibralfaro") at right. The two were connected by a

zigzag ramparts called the "Coracha." Think of giant (and

grotesquely shaped) barbell sitting on a steep slope.

This fortification is really two castles built several

centuries apart. The older, drawn above, is called the

Alcazaba and this view looks down to the foot of the hill

which rises steeply above Málaga. Note how the

Mediterranean (now long receded) then came to the edge of

the fort. Double walls with ramparts surround the entire

site, with moats in some areas. Since each was built at

the then state-of-the-art technology, we see a bit of the

history of medieval fortification with this restoration.

Above we have the older fort at the base of the hill.

It's a quadrangle -- typical of the Moors forts. Its

original intent was to defend Málaga from pirates,

explaining its proximity to the sea. It was completely

rebuilt in the 11th century as the central Moor power in

Córdoba splintered.

Here's a model showing the cathedral (at 7 o'clock

position), and the older Alcazaba at 6 o'clock) on the

hill. Nearly atop the mountain at about 11 o'clock is the

Castillo (Castle) de Gibralfaro. The spindly double wall

connecting them is the Coracha. Its zigzag shape allowed

defenders to protect it without having to build towers

jutting out from the wall.

Entrance

Let's return to the bottom of the hill and enter the

Alcazaba. The fort started in the 9th century as a simple

watchtower ("Almería" in Arabic). In the 10th

century, Málaga was enclosed in a wall and this

became a citadel, ushering in the 11th century splendor

of a Taifa kingdom as the central Moor power in Cordoba

deteriorated into multiple city-states. In the tenth

century Abd al-Rahman III surrounded the city with a wall

and built his Citadel. The eleventh century was a time of

splendor as Taifa kings expanded the fort. One of them,

Al-Mutaslm, built his palace within the walls. Centuries

later, Granada's Nasrid kings would revitalize this fort

and palace complex.

The entrance into the Moorish Alcazaba is protected by a

number of zigzagging curtain walls and gates designed so

that attackers would have difficulty getting any momentum

with either horsemen or battering rams. When the Nasrid

kings upgraded this entrance on an older fort, they added

such then state-of-the-art castle defenses.

Here's another abrupt turn.

The lower fort was originally built with limestone which

deteriorated quickly in the salt spray. The Nasrid

reconstruction replaced much of this with masonry using

stones as seen here, held together by horizontal layers

of brick. The piece of a pillar here was probably a

remnant taken from the Roman theater below.

This model shows the set of twisting gates and passages

allowing castle defenders many opportunities to stop an

onslaught before the enemy could reach the flat Patio of

Arms (the garden at top) where the munitions would be

stored in the lower fort.

This interior gateway is called the "Puerta de las

Columnas" after its columns (stolen from the Roman

theater at the bottom of the hill.) The walkway doubles

as drainage ditch during rainfall.

Swatting the Sultans

The Sultan who built Málaga 's Alcazaba was Yusuf

I, the 7th ruler of Granada's Nasrid dynasty that ran

what remained of Moorish Spain after the Christians took

the once great city of Córdoba in 1236. While

Yusuf I had great interest in architecture and left some

beautiful works behind in the Alhambra in Granada, his

impact here was more practical. He was fighting the

Christians and needed strong forts to withstand their

sieges.

In 1354, a maniac with a dagger killed Yusuf in a Granada

mosque while he prayed. This explains why so many mosques

have gazebo-like screened areas to protect their rulers

who must prostrate themselves at the conclusion of the

Islamic prayers. Yusuf was 36 years old and was succeeded

by his 16-year-old son. Sultaning was a pretty hazardous

occupation.

After Yusuf I, the Nasrids continued destroying each

other, allowing the Christians to take their cities

one-by-one. Finally the Christian king of Castile, Peter,

lured Yusuf's nephew who was ruling as Muhammed VI into

his kingdom and subsequently made a gift of his

red-haired head to Yusuf's son Muhammed V -- who was then

restored as sultan of Granada. Pedro, nicknamed "the

Cruel," kept the torso. With family like that, fortresses

such as these don't work all that well.

The Interior

The above view shows an interesting wall at the left,

part of the old lower fortification where brick and

mortar replaced the earlier limestone. This nearly

serendipitous conglomeration of masonry, mortar, and

stone does not make for a pretty castle wall! The newer

fort rises on the mountain at center left.

Gardens of various sizes fill the many courtyards as the

fortification climbs the hill. In the distance is the

cathedral's bell tower. This broad and level area is the

Patio of the Arms (Plaza de Armas.)

Siege the

day

Fernando and

Isabel conducted a long siege here on their route to the

coup-de-grace at Granada. Isabel personally attended this

siege and stipulated that the soldiers must follow strict

rules against swearing, gambling, and frequenting with

prostitutes. The long siege got even longer! But Isabel

did much for her soldiers including setting up what was

probably the first-ever field hospital. (This probably

was not enough recompense for her conscripting all males

in her kingdom between 20 and 70 years of age to

fight.)

Isabel's presence at Málaga was somewhat unusual

but requested in this case by Fernando: the Moors had

spread a rumor among the Christians that Isabel was

nagging Fernando to withdraw. He wanted to show

one-and-all his Queen's unswerving commitment to

Málaga's capture.

The fleet of Aragon blockaded the harbor and the

Christians were able to defeat the Moors' relief armies.

Isabel convinced her husband to wait, as she wanted to

minimize casualties. Eventually the defenders would be

starved into submission.

A Dervish fanatic convinced the royal guards that he

could prophesy the future for the king and queen; but it

was plot and he attacked them. Fortunately in these

pre-media days, he didn't know what Ferdinand and Isabel

looked like -- and so stabbed the wrong couple. The

Christians graciously returned him to his compadres in

the Alcazaba -- one version says by mule but another more

interesting account was by catapult. Often attackers

would send plague victims over the walls the same way in

the medieval version of biological warfare, long before

germs were discovered. It is possible that the Black

Death which eventually wiped out a third of Europe was

introduced onto the continent via catapult. Are humans

the ultimate weapons of mass destruction?

Most medieval war consisted of long sieges against towns.

Most ended with the attackers giving up and leaving or

the town negotiating surrender which gave them many

rights. (Often the Muslims would be allowed to live in

the conquered city under Moslem law.) Not so here where

the attacking Christians numbered 60,000 to 90,000

troops.

But Málaga held out too long and Ferdinand wanted

to demonstrate why that was not a best practice. When

Málaga surrendered unconditionally, Fernando was

brutal.

It was not really the townspeople's fault as they wanted

to surrender early and made sure Fernando knew that

through their emissaries; but the garrison was headed by

an obstinate Moor named Hamet Zeli who refused surrender

for four long months. Grain ran out. The town ate its own

dog food, and then its dogs and horses and cats.

Water, but little food

As in any good Arab garden, water flows to nourish this

urban oasis. This channel starts near the top of the hill

where a 40-foot deep well ensures the castle would never

surrender due to thirst. In fact, this fortress, thought

to be impregnable, held. But blood flowed here with the

water after the surrender to the Christians in mid-August

1487.

Much of the town was enslaved including 50 girls sent to

the Queen of Naples. One-time Christians who had long

before converted to Islam and were called "Renegados"

were tied to stakes and used for target practice. Jews

were ransomed. Fortress Granada watched and learned --

and negotiated a much more favorable settlement to its

siege 4 years later including a favorable exit strategy

for the Sultan.

Fortifications

The outer wall (left) and the inner (center). The stubby

merlons at top do not seem to have been fully restored.

But let's look at these crenellations a little more

closely...

These pyramid tops are typical of the Moors merlons.

These are quite wide; in Roman times, merlons were no

wider than the width of a single defender...

... As defense technology improved and more weapons

needed to be shielded, merlons widened to protect

crossbowman and their larger equipment. Note the square

towers protecting the corners. Behind the modern high

rises of Málaga climb the foothills.

A historical first

A bit of war technology history was made here as many

historians feel the siege of Málaga was the first

time attackers used artillery, which up to that time was

pretty much confined to stationary cannon inside forts.

As siege artillery improved, merlons and castle walls

became obsolete. Queen Isabel --a visionary in many

ways-- was the driving force for introducing the northern

European cannons into the Spanish war of Reconquista. Her

logistical brilliance provided the men, material and road

building needed to transport huge artillery to castle

walls. Her guns were very crude 12 foot-long

rectangular-shaped shafts of iron clamped together in a

circle and called "lombards." Crude but capable of

propelling 140 cannon balls per day up to a foot in

diameter at walls such as these -- if only they could get

into position. The siege of Málaga was a game

changer, not unlike Nagasaki.

By the end of the war in 1492, Ferdinand and Isabel had

deployed over 200 of those primitive cannons, mostly

hired from Northern Europe. (Ferdinand was smart enough

to couch this as a holy war and got the Pope to pay for a

significant portion of the cost.)

While the offensive artillery had some success against

the outer set of town walls, these inner walls held --

the Nasrid garrison eventually had to surrender or

starve. Napoleon said an army marches on its stomach.

Here the defense failed for the same reason. As they ran

out of food, Malagueños also ran out of

negotiating capability and surrendered unconditionally.

Not a good idea for an impatient King like Fernando who

still had the mighty fortress of Granada to take. He

wanted to set a harsh example of why not to wait out a

siege.

The Palace

But besides being a fort, this was a palace for the

Nasrid rulers when they were in town (perhaps on a visit

or perhaps fleeing their own family members in

Granada.)

While this is not quite the Alhambra of Granada, it is

considerably less crowded and has much the same layout

including 3 separate courtyards. Unlike the Alhambra, we

find here excellent (even if Spanish only) wall signage

explaining Nasrid architecture and palace life.

Note the tower above which, with its views -- port, sea,

Africa, Gibraltar -- would provide an even better vista

than the Nasrids had in their headquarters at

Granada.

This portico...

...leads to another of the three courtyards of the

Nasrid Palace. This area also serves as a museum of

ceramics stretching back to Phoenician days.

A stop in the scenic mirador gives us two views of

luxury. We stand in the Sultan's viewing point and

see...

... a distant cruise ship berthed in Malaga's port. If we

only count creature comforts, most of us live better than

the Sultans...

...and our chances of assassination are generally much

less. When this palace was built, most Sultans feared

their brothers. Those in Istanbul eventually figured out

the solution...

... when

they

assumed the throne, they had all of their brothers

killed.

Above and below are close-ups of the pillars and

arches.

This set of triple arches was erected in the 11th century

as the Córdoban Caliphate disintegrated as a

political power and the Moor states spun off into

city-states called Taifas. Not all of the stucco

decoration has been restored here.

Above this pillar was considerable calligraphy which

typically has not been restored. The ochre support above

it shows faint details of an abacus.

An elaborate multi-lobed portico on a blank, but probably

once highly decorated, wall. This door may lead to the

mirador or viewing tower.

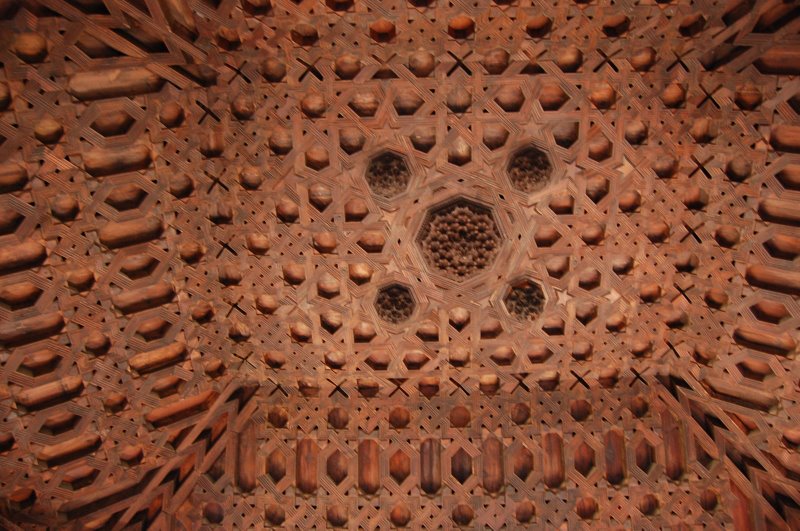

Here's two ceilings, this one the traditional Mudejar

inlaid wood from the 16th century made in homage to the

great ceilings found in Granada's Alhambra ...

...and the low budget version made of brick (actually

painted brick!)

Note (above) the vegetable decorations around the top of

this capital. Above these would typically be calligraphy

reminding the rulers that their power and victories came

from God.

In the rough centuries that followed the collapse of the

Caliphate in Cordoba, Málaga became capital of its

own small kingdom 4 different times.

This area also included Arab baths also fed from the

well. Let's return now to the fortifications.

The Corach

Here's a view of the Corach, the walled passageway

leading from the lower to the upper fort on Mount

Gibralfaro.

Here's a back view of the Alcazaba. The upper castle is

called the Gibralfaro which means "hill of the

lighthouse." The Moors once had their atalaya (signal

fire) at the base of the hill.

The Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans all had forts on this

site before the Moors built theirs. As late as 1765, one

of these towers was outfitted with a bell to warn

Málaga of pirate attacks. Remember those pesky

Barbary Pirates and the shores of Tripoli? It took 7 US

Marines to do the job on those rascals. Lately we've been

having more help and less success.

This watch tower still takes a commanding view over

the countryside with its brick-brimmed derby hat.

The area of the upper fort (Gilbarfaro) has been restored

as botonical garden.

This westward view shows the fortress, the cathedral

beyond, and the mountains hazily in the distance.

The Corach, the long connection between the upper and

lower forts, zigzags down the hill, allowing for its

defense without towers jutting out from it.

Another view of the ramparts, merlons, and a

watchtower.

Let's now trek down the hill and check out the

Christian's most important building -- the Cathedral.

Please join us

by

clicking here.

If you have good bandwidth, Please join us in

the following slide show to give the

Málaga, Spain the viewing it deserves by clicking here.

|

|