| You may prefer to see these pages as a photo slide show which contains the same text but presents the pictures full screen size. If so, click on the slides presentation at the right. |

Split started life as a retirement villa for a retired Roman Emperor -- and ended up as the Dalmatian coast's largest city as well as its economic and cultural hub. The important Roman town was four miles away with all the comforts of a provincial capital -- and because of that, a target for the invading Slavs. When that capital fell, some of its inhabitants moved inside the palace's protective walls. Sons of these squatters are still here -- and Dalmatia's greatest city grew outward under Venice and a huge succession of other rulers.

Besides being the economic and cultural heart of the Dalmatian coast,

Split is its transportation hub. This includes the modern freeway,

railways, and as we see here with its scenic harbor -- the sea. The

location of this busy port is a bit of an anomaly since a much larger

and better protected harbor (and close to the fresh water of a river's

mouth) lies only 4 miles to the north.

That location was perfect for the Romans who located the provincial

capital of Dalmatia there and called it Salona. The Avar Slavs

destroyed it (and just about everything else they could get their hands

on) in 614 ACE. Residents fled to the islands -- and to a huge

fortified palace that a powerful Emperor had built around 304 ACE.

They've been squatting ever since, and the town around them expanded to

become Croatia's largest coastal city with about 200,000 people.

If we moved it directly west to North America, it would be north of Milwaukee and south of Toronto -- and everyone would complain about losing their Mediterranean climate and all those palm trees.

At the center of the topographical model shown above, we see the Jadro River draining into the Adriatic and moving past the old town of Salona, the Roman capital of their Dalmatian province. This was a major city with coliseum, temples, and all the other accoutrements of a Roman provincial capital. Below at #2 is the sheltered inlet where the Dalmatian-born Roman emperor Diocletian built his retirement fortress about 4 miles southwest of the capital.

In 614 A.C.E., the Aver Slavs wiped out Salona and while much of its population retreated to the islands, many moved down to the old palace with its protective walls. The good news is that they never left -- and so the place still stands rather than having been turned into a recycling quarry for medieval buildings. The bad news is that they never left, and what's left of the palace is a mishmash of residences and cafes cluttering up what may be the world's most significant Roman residence still standing.

Above is Split's master builder: Diocletian is now consigned to the basement -- a location that survived intact only because it was filled with trash.

He was probably the first to wear the gold crown and forbade anyone to wear purple except the emperor. A religious conservative, he promoted the idea that the emperor is a logical extension of the gods and claimed that he himself was a descendant of Jupiter, the alpha Roman God. Therefore it's no surprise that the Christians who eventually won out revile him. (Diocletian exacerbated the problem by conducting the only empire-wide persecution of Christians.)

Historians are more kind to Diocletian as his reforms probably extended the hegemony of the Western Roman empire for another century. When he arrived, the barbarians were at the gate and probably would have wiped out the empire. Instead, Diocletian reestablished order (which meant a return to the traditional gods, not those new ones of the upstart Christians.) He negotiated with Iran -- only to have them break the peace.

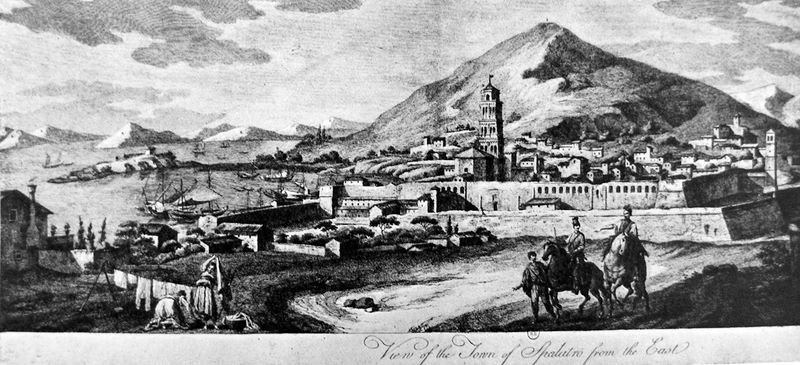

Above is a medieval view of Split. The Venetians added the star-pointed fortifications when they dominated Dalmatia for 4 centuries. The nearly perfect rectangle on the right side is the house that Diocletian built. It held 10,000 people including his protective army. Well fortified, it protected the population who moved in after the Avars (a Slavic people) destroyed the important Roman city just north of here in 614 ACE.

Diocletian built well; a succession of invaders through this area never penetrated the 6-foot-thick walls of his palace. What was the suburb became the city.

The old general Diocletian's rectangle resembled a Roman military camp

(castellum) which was laid out precisely the same way. In camp, a

soldier's tent was always in the same spot no matter where the

battilion moved or what the terrain was. Diocletian's walls were high

with a gallery at the top. Each wall had a gate at its center,

including the sea gate at right. These gates led into two cross

streets, again just like that of an army camp. Note that these grand

avenues have colonnades on either side.

The soldiers lived on the northern land half of the complex, and the emperor and his religious regalia on the sea side. The green designates the gardens which he loved. The projecting octagon is where he was laid to rest -- until the Christians took over and made it a cathedral honoring one of his prominent victims.

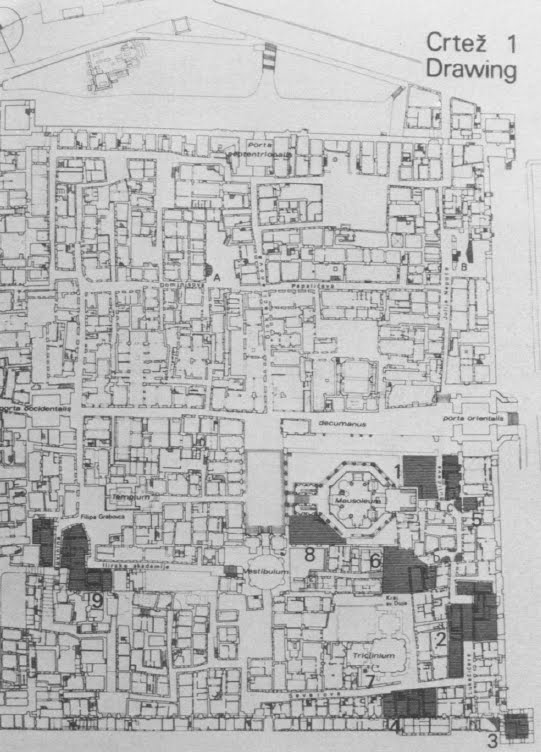

This drawing was made in 1757 by an important architect we'll discuss in a few more slides.

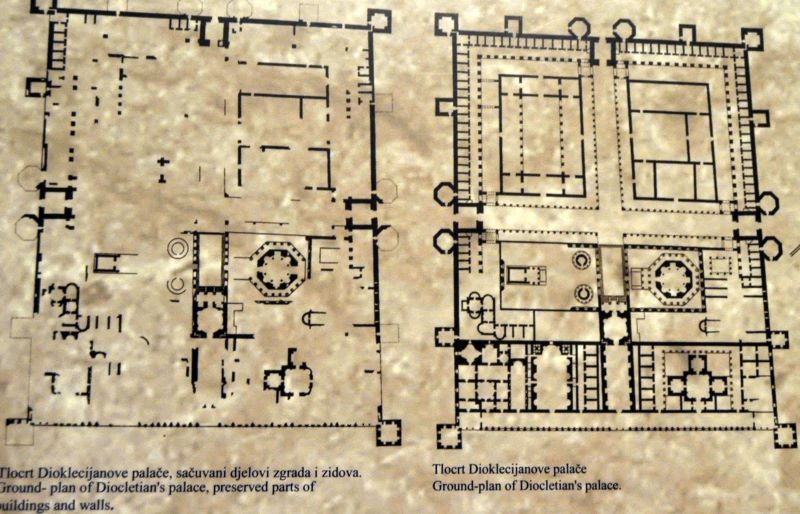

Emperor Diocletian was the first to voluntarily retire. He did so after

spending 10-15 years constructing the villa depicted as the trapezoid

at the right -- about 8.5 acres in all. At left is the map of the

"preserved" palace after 1400 years of being a town center. It's filled

with hundreds of buildings added later, but this representation shows

what's left of the original.

Diocletian loved his retirement. When the Senate asked him to return to power as the empire was collapsing, he told them he preferred to stay here and grow cabbages with his own hands. His fortress-villa served as a prototype for Roman residences in the territories where Rome wrestled with invaders. Its DNA is that of a military fort (castrum) -- a rectangle further subdivided into fourths by two cross streets and protective walls, here about 6-8 feet thick. Except for the twin hexagons that protect each land gate, the towers were squares -- somewhat unusual as square towers were more easily destroyed by enemy assault weaponry.

So much for idealized models. Above is what we see from the sea in

Split: It's tough at first to find the palace through the trees -- and

drying laundry, ugly windows, etc. A closer look reveals columns

embedded in the wall as well as one of the square corner towers. (Many

of these today are being restored and leased to banks and

restaurants.)

Once you would arrive here by boat and enter through a beautiful marble gate, but this area was filled in to create a quay. Today it's nicknamed "the Riva" and is lined with restaurants and palm trees.

Diocletian was from a humble Dalmatian family and his father may have been a slave. (Slavery was quite common along this coast up until the 13th century, and our English word "slave" is derived from the same root as "Slav.")

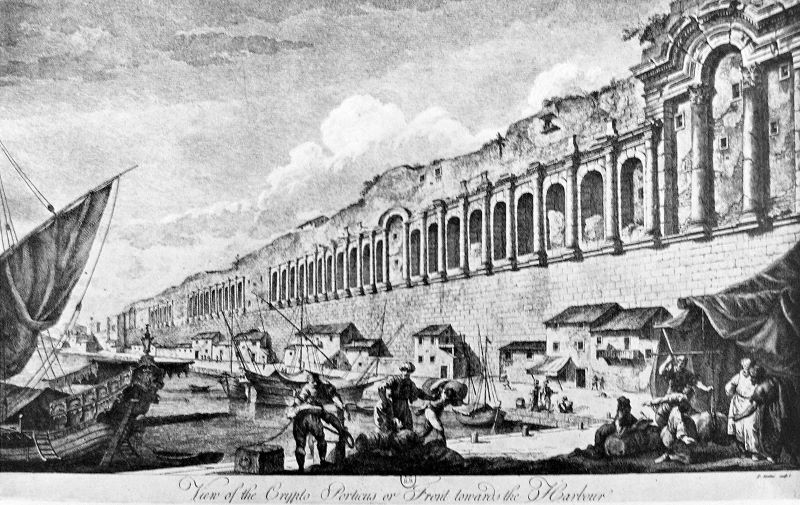

The Scottish architect Robert Adams made the above drawing of what he

called the "Crypto Porticus" along with the birds-eye-view we saw a bit

earlier. As part of his education, he took the "grand tour" of Europe

and stayed here for 5 weeks in 1757.

Since Adams made this drawing, the arches have been bricked in with smaller window opening and taller buildings have been built behind this wall. (So thorough was Adams' work that the Venetian governor thought he was spying and nearly deported him.)

At upper right is the sea gate (called the "Bronze Gate") where Roman galleys would deliver VIPs to visit the retired Emperor.

Adams published his notebooks seven years later in a book that heavily influenced the classical architectural revival that would become the rage while the kings George ruled England. Adams himself became an important architect in his own right.

Some argue that Adams became the most important British architect of

the 18th century. That's something for a man valued more for his

remodeling of interiors than commissions for entire buildings. Above we

see the first neo-classical project in London, started in 1768 by Adams

and his 3 brothers (who like their father, were all architects).

The Adams family appears to have borrowed the vaulted terrace on the water from the design Robert sketched in Split 11 years earlier. These 24 unified structures were called the Aldelphi Buildings and George Bernard Shaw lived in one of them and did write about architecture (and so much more). Since Shaw's day, the Adelphi complex has been Houstonized (i.e. torn down in the name of progre$$.)

Adams' influence was immense; many of the Federalist buildings of our

founding fathers were directly influenced by his theories. They viewed

their new republic as following in the traditions of the republic of

Rome and the Greek democracies. When you destroy the old, find an even

older model and argue you are returning to that. What our founders

borrowed from the appropriately named Adams, he, in turn, borrowed from

his short visit to this palace. We are fortunate that Adams could

extract the classic essence from walls corrupted by 14 centuries of

daily life.

Modern archeological excavations began here in 1954. Because of the difficulties of displacing residents who think they live in a city, not a museum, work is slow and it will probably be a long time before this best-preserved Roman palace is fully excavated -- if ever. Typically residents are lured from this palace by promising them modern apartments elsewhere with more creature comforts. (Who needs history when you can have a walk-in closet?)

Imagine, as you must, this fortress. Its rectangular walls are

crowned by the colonnade we see above. Inside are two long cross

streets which themselves have elaborate colonnades on each side as we

see at lower center through the east gate.

After Diocletian's death, Roman nobles lived here and some of the northern buildings which would be to the right of this street -- and which had served as warehouses and barracks for the army -- became a textile factory to make uniforms for the Roman army.

Besides the sea gate, each wall had its land gate protected by

hexagonal towers. Today the east side of the complex is the scene for a

daily market. While the walls are generally still standing (but have

typically lost the colonnade on the upper floor as we see here), their

towers are long gone. We'd suspect that the stones migrated behind the

walls and found themselves in some of the hundreds of buildings added

after Diocletian died.

Once siege armies figured out how to use assault cannons, such towers became useless for defense -- and fair game for recycling. Some of these towers have been restored (or even rebuilt) and are now occupied by banks and restaurants.

The fact that an Emperor had to build walls around his provincial villa -- and provide barracks inside for a small army to protect him -- shows that by Diocletian's day, the empire was under assault from the invaders who would eventually destroy it in the West. After all, the provincial capital was only 4 miles away.

Here we are inside the complex looking back at the east gate we saw on

the previous slide. This area is treated as living space as is

evidenced by the grey hotel rising right inside the palace.

Archeologists feel that they may never be able to excavate the entire

palace due to the issues surrounding moving tenants who have been

"squatting" here for at least 1400 years. Since 1968, the University of

Minnesota under the aegis of the Smithsonian Institution has been

assisting the Town Planning Institute of Dalmatia in conducting

excavations.

Think back to Diocletian's day when the broad east-west street would have a colonnade and porch on each side to protect from the elements.

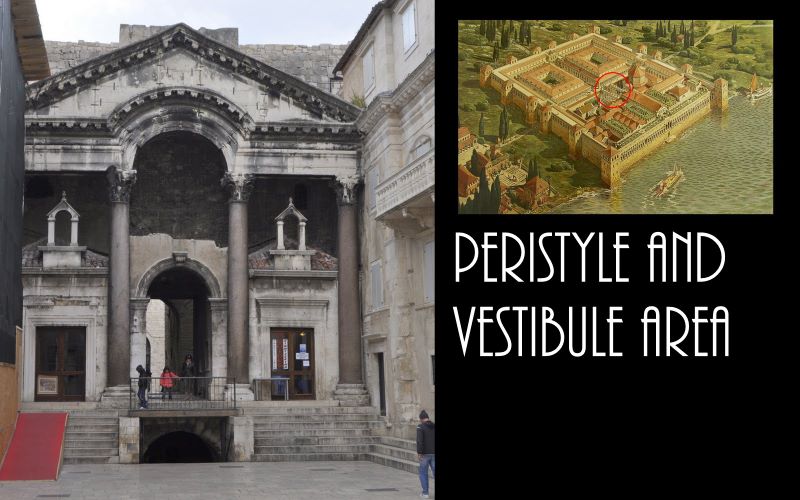

The two main axes cross at a square called the peristyle that was

converted to the cathedral square after the north and south gates were

closed during the early middle ages. These elegant Corinthian

colonnaded arches line each side of the two main streets providing a

long gallery through the palace.

The peristyle was the public center of the palace, equivalent to the

forum of a Roman town. Here Diocletian would make his public

appearances. Behind the central open arch is the domed vestibule where

visitors would be ushered into Diocletian's living quarters. If they

came by land, they would enter through the elaborate North gate and

directly approach this building after walking through the wide

colonnaded street. To the left rose Diocletian's tomb (now the

cathedral) and at right were three temples -- one of which survived as

a baptistery.

Ignore the plywood and grime and, instead, put on your history glasses

here to imagine your entrance from the North, stopping here at the

front of the retired emperor's palace. Colonnades rise on either side

as they might in a small town's forum. Each side once had its sphinx,

brought here from Diocletian's campaign to quell an uprising in Egypt

in the late 3rd century.In a way, this could symbolize today's historic

Croatia. Classic jewels rising out of centuries of grime and dust --

and hoping to stimulate their economy through tourism.

Visitors who love history can come here; those looking for sun will find only 100 yards from here the dazzling blue Adriatic trimmed with white beaches. A spot suitable for for an emperor should be good enough for a tourist.

Above is a detail of the pediment rising above Corinthian pillars. This

is somewhat unusual as the entrance arch projects into it. The palace

architects are unknown but may have been Greek since two Greek names

are engraved within the walls -- and this structure has a classic Greek

feel to it. Some might feel that's a bit ironic as this is an icon of

Roman architecture. But Romans were always happy to pragmatize Greek

ideals.

The vestibule contains a magnificent dome crowned by the open oculus which reminds travelers of the Pantheon in Rome.

This appears to have been originally covered by a cupola and the walls

were long ago covered by mosaics, making this a quite elegant place to

wait until the former emperor decided to grant you an audience.

As you might expect, this makes an ideal space for performances during

festivals. At other times, a cappella groups perform here and sell

their CDs to tourists. If you want to hear a sample, click here.

Dalmatia has a popular a cappella tradition called "Klapa." Although it seems a bit like traditional folk singing, it first appeared here in the 1960s. When the group is male, we get two tenors plus a baritone and bass. Quite pleasant although not what we think of as 60s music!

Here's traces of another Klapa group we found inside the palace walls

-- and one of their biggest fans who got stuck in the 60s. . (Klapa is Croatian for "group of people. ") Maybe she too will be someday be remastered and rediscovered.

This street scene is typical with narrow alleys separating centuries of added shops and residences.

Here we look north from the vestibule. At left we see the elegant

colonnade with a baroque building filling in its arches. In

Diocletian's day, to the left of those arches would be three temples

whose purpose would be to argue that the tomb to the right contained a

deified emperor. Long before the Gothic cathedrals, we had theology

through architecture.

The construction that followed Roman rule provides its own set of

challenges: would you tear down this building, peaking through

Diocletian's colonnade, to restore the palace to its Roman roots? While

this site is an outstanding Roman site, it contains medieval,

renaissance, and baroque structures as well. As native Croatian

architectural scholar (and one-time University of Texas professor) Ivan Zanic asks, what should be preserved?

Ready for another religious war in stone? This colonnade-enwrapped

octagon at center is 1700 years old and was built as the emperor

Diocletian's tomb. This most vilified Roman emperor's mausoleum still

stands because it was converted to a cathedral honoring an early bishop

Domnius (or Duje) who was martyred in the Roman's last great campaign

to stamp out Christianity. It's known as the Diocletianic or Great

Persecution since it happened on his watch at the beginning of the 4th

century.

This man who tried to further deify the emperor ended up on the wrong side of history; his successor and adopted son Constantine would make Christianity the state religion a generation later. But the boxcutters of the September 11 terrorists killed nearly as many Christians as did Diocletian's swords: around 3,000. In Diocletian's day, Christians numbered about 6 million, about 10% of the population. A lot of lions went to bed hungry.The bell tower was built much later.

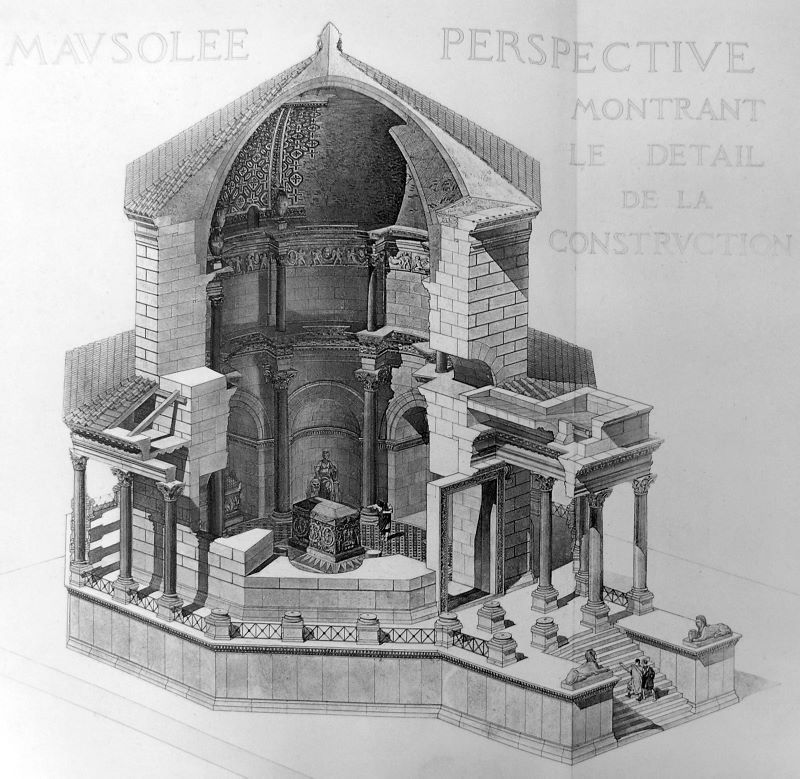

Photographs were not allowed inside Diocletian's octagonal mausoleum

(now the cathedral) but we found this old drawing showing its

internals. Most of the double row of columns are originals. They

support a frieze with reliefs of Eros and Diocletian and his wife

Prisca (who may have been a Christian herself.)

In the 7th century, Diocletian's remains were evicted and replaced by those of the Dalmatian bishop Domnius ("Duje" in Croatian). Not much has been replaced of the Roman structure but a few Christian elements have been added such as Romanesque 13th century choir stalls and a 1427 altar by Bonino of Milan (who visitors to these pages undoubtedly remember from his statue of Roland and Dominican decorations in Dubrovnik. (If you'd like to see those, click here.)

Here we see a remnant of the Corinthian colonnade that lined the two

intersecting thoroughfares along with the six-story Gothic bell tower

added much later. Today this tower is the symbol of the city: a

Christian tower refuting the emperor who inadvertently put Dalmatia's

greatest city on the map as he failed to deify himself. Sic transit gloria imperatori!

Here are some of the details (and lightning rod) from the bell tower.

This Romanesque structure was primarily built during the 12th-14th

centuries when Split was an all-but-independent medieval commune. It

was further remodeled at the beginning of the 20th century.

The mausoleum/cathedral is surrounded by its own octagonal colonnade.

Tradition holds that during construction, this was a prison for the

Christians whose Great Persecution started in 302 ACE. Diocletian

retired and moved into his palace 3 years later. He began to use this

tomb in 311 -- one of the very few Roman emperors in the 3rd and 4th

century to die of natural causes -- and the first ever to retire. While

he probably added a century to the lifespan of the Western Roman

empire, his contributions allowed the eastern (Byzantine) empire to

last a millennium after his entombment here.

In attempting to restore the traditional Roman gods -- and place

himself in their sphere -- Diocletian built a colonnaded temple to

Jupiter, the head of the Roman gods and one to whom he claimed a

special affinity. Two other temples have been torn down here, but this

survived by being baptized-- and baptizing others through total body

immersion. At left is a headless sphinx.

Jupiter's statue has been replaced by this 1954 statue by Croatia's greatest sculpture, Ivan Meštrović, who spent his summers in Split before escaping to the new world.

The Baptistery ceiling is quite elegant. As emperor, Diocletian held

that he was a descendant from Jupiter. (This from a man probably the

son of a slave!) The palace symmetry with the deified emperor's tomb on

the east side and the temple of Jupiter on the west would support his

attempt to merge secular and religious authority.

The font is in the shape of the cross and is large enough for total

immersion, a bit unusual in a Catholic church. The stone reliefs on its

side date from the 12th century...

...and include a Croatian king on his throne with suitably supine supplicants...

...as well as this more abstract star with birds and flowers. These

abstract reliefs were quite common along the Dalmatian coast during the

middle ages.

One of the few areas that is free of residents is the basement -- which

was a 1700 year old garbage dump until excavations removed the rubble.

Their footprint suggests the layout of Diocletian's private apartments

above which have been hopelessly partitioned.Today this space is often

used for concerts

The basement area runs below the emperor's quarters. These stones are precisely cut and stacked; who needs mortar?

This southeastern section of the palace was one of the major focus

areas when the Americans joined the archeological effort in 1968.

As later residences were demolished, some of the foundations for

Diocletian's private apartment walls became evident. Still, much of the

original layout is still unknown.

The basement contains many half and full domes showing much more humble

building materials than the white marble of the palace above. Most of

that marble came from nearby islands such as BraÄ and Trogir.

This brick arch still supports the palace above after 1700 years.

With so much additional building over the centuries (and so little

signage), it's difficult to tell what was the original palace and what

has been added.

This drawing shows that, to a large extent, the palace is now a set of

walls with a few reasonably preserved monumental buildings. Most of the

warehouses and barracks of the northern end have been replaced by a

hodgepodge of small buildings, as has much of the south. In 1955, the

palace had 540 buildings with houses accounting for about half of that

number and housing about 3200 people.The dark areas show some of the

restoration work, typically tearing down buildings and looking for

Roman foundations, but at times building up towers long cannibalized

for their building stones. Thanks to Dr. Ivan Zaknic for this drawing as well as much of the information about the Palace's restoration.

Work was added to this late Roman residential masterpiece from the

early Medieval, Medieval,Renaissance, and Baroque periods. Nature has

been embellishing the cracks as well.

This is probably the interior of the south wall showing the white

BraÄian marble arches looking through to the sea -- interrupted by

later stone and window work. Many Croatian tour guides brag that the

marble for the United State's White House (perhaps now it can be

renamed the "rainbow house") came from the Dalmatian islands. It didn't

(although even the New York Times was fooled about that for a while.)

However, the neo-classic architecture revival which gave that and many

other federalist buildings their style came through Robert Adams from

this villa in Split. We got the shape from here, but not the stones.

Common folk have been living inside the palace since the Slavs invaded.

Today, the citizens of Split consider this to be a living city, not a

museum. Despite being a UNESCO designated historic site, the city

fathers decided to build a parking garage here a few years back.

Fortunately, a public uproar stopped it early on.

The blight occasionally produces colorful bursts of daily life....

...that delight the photographer as much as they irritate the

historian. Since most Croats are Christians, Diocletian's palace

today probably holds as many Christians as he once martyred. And they

don't mind airing their clean laundry in public.

Let's look at the palace's two other gates, starting with that on the

west. Beyond this point, the medieval and Venetian town grew and

finally Venice put a star-shaped barricade around the entire complex.

Here, as at the east gate at the other end of this street, we see a

square gate, capped by an arch, with a gallery above.

The west gate is the best preserved and is called the iron gate. (By

now you realize that each gate is named after a metal.) The 15th

century clock tower tells time in 24-hour increments. As the town

expanded westward from the 16th century onwards, this became the most

important gate into Diocletian's palace. The town administrative square

that we will visit in a moment grew from here into the newer portion of

the town.

Let's end our palace visit where it would have begun in Roman times as

we would enter from land through the north gate. To impress visitors,

this would be a magnificent entry, most probably bedecked by statues

and bristling with soldiers and the trappings of empire. Unfortunately,

it was walled in during the middle ages, severely restricting the flow

along the palace's perpendicular axes. While recent restoration has

reopened it, the stone work obviously needs further work. This Golden

Gate greeted land visitors and ushered them down the north-south axis

road called the Cardo to the vestibule, temples, and emperor's

apartments. Once it was perhaps the grandest gate in Dalmatia.

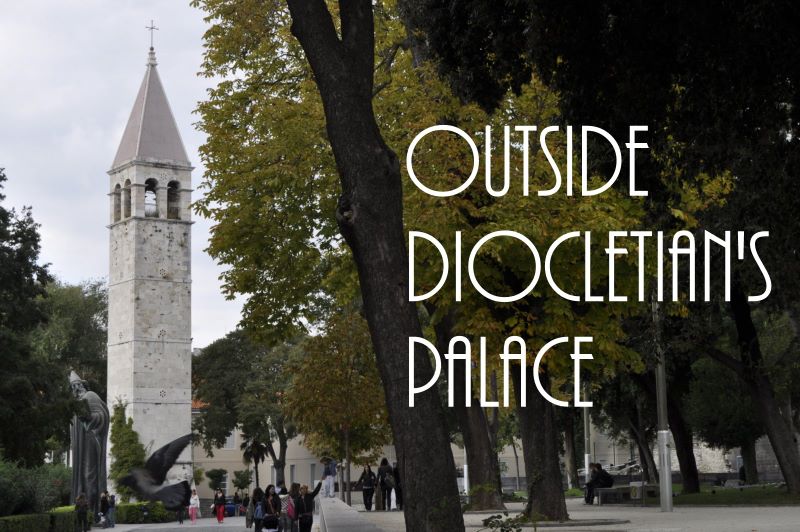

Let's leave Diocletian's Palace now through the North Gate where, if we

were Roman VIPs, we would have once entered the city. Because of the

Ottoman threat in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Venetians built a

large star-shaped barricade around both the palace and the newer town.

Many years later when these were torn down, they provided room for the

park we see at right. Just to the north of the palace wall, we see two

strong vertical elements, the tallest of which is the tower of a now

long-gone Benedictine Monastery. Before that at the left we see ...

...what I think is one of Ivan Meštrović's most impressive

sculptures. This depicts the 10th century bishop Gregory of Nin. Many

of us think that Vatican II (with its theological rock

stars Wojtyła and Ratzinger ) brought the native language into

the Roman Catholic church in that strange decade some of us remember as

the 1960s.

Long before in 926, Bishop Gregory battled popes to win the right for

his fellow Croats worship in their own language -- and won. For a

millenium before Vatican II, Croats prayed in Croat while the rest of

the Roman Catholic world prayed in Latin. Ite, missa est!

This liturgical use of Croatian helped keep the country staunchly

Catholic even while all sorts of other nations were running it -- and

it helped keep alive Croatian language and culture.

Commissioned in the late 1920s to commemorate Gregory's 1000 year anniversary, this statue started out in the Palace peristyle; but the Italians moved it outside during their WWII occupation. The toe is shiny from tourists kissing it. Doing so makes wishes come true. Better a bronze toe than a bachelor frog, perhaps.

Just west of the west (iron) gate we encounter the large civic square

anchored by this 15th century town hall which combines flamboyant

Gothic upper levels above Renaissance galleries -- not unlike the civic

architecture in nearby Dubrovnik. (Please excuse the lens distortion

here.)

From 1924 through 2004, this building housed Split's Ethnographic Museum, a very important institution given Split's centrality to the Dalmatian coast and the number of objects moved here from the islands. (The museum has since moved inside the palace behind the vestibule.)

Here's another elegant building edging the People's Square. Such wide

expanses are woefully absent within the adjacent palace where most

space was devoted to one of the nearly 500 buildings erected after

Diocletian's death.

About 200 yards to the west, we encounter Marmontova Street -- quite

the pedestrian walkway with a bit of modern sculpture reminding us that

we are in the 20th century.

Like the rest of the old town, this area has been completely

pedestrianized. This part of the city is completely unlike the cramped

palace, but it is also the work of a general. (Diocletian, of course,

became emperor by being a very good general first.)

Marmont street leads to the sea and was the western boundary of the

Venetian town. Wide and adorned with elegant residences, the street is

named after the general who decided the town was safe enough to destroy

the Venetian walls. Once removed, parks and esplanades such as this

sprung up and opened Split to its glimmering seascape.This vision was

that of Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont, Napoleon's

aide-de-camp and most stalwart supporter/traitor.

Nearby Dubrovnik invited the French to help defend their city against the Russian fleet -- but they stayed; and Marmont became Duke of Ragusa. Viewed with disdain by the French, Marmont is well remembered in Dalmatia for being a good governor and for creating public works such as this street. (You may recall that about this time, Paris was tearing down its city walls and creating those lovely boulevards. "Boulevard," of course, is the French word for bastion.) With its lack of cars and sea views, Rue Marmont is easily as pleasant as most Parisian streets.

This sketch by the architect Robert Adams during his grand tour in 1764

looks to the west and shows the star-shaped Venetian defenses that

Marshal Marmont would tear down a couple generations later. The bell

tower here looks complete -- but is not as rectangular at the top as we

see it today. The harbor frontage was added on after the Jews, expelled

from Spain in 1492, settled here and helped make Split the center of

Dalmatian commerce.

Now back to Marmont Street where we find this 1903 Secessionist

(=Croatian Art Nouveau) building by a local architect named Kamilo

TonÄić. It was built over a natural sulphur spring and is called the

"Sulphur Spa."

Here's one of the upper decorations on TonÄić's building. Kamilo

TonÄić went on to be an important Croatian industrial designer and

brought such craftsmanship to manufactured articles for everyday use.

This building alone might make TonÄić' remembered in Split, but he made an even greater contribution by championing the founding of the Ethnographic Museum and serving as its director until 1944 -- including saving most of its contents from the Nazi occupation.

Walk down Marmont Street and turn right at the elegant fish market -- and you get to Republic Square.

Not without reason does this elegant neo-Renaissance square remind us

of St. Mark's Square in Venice (without the crowds.) When Marshal

Marmont tore down the Venetian defenses, he put a garden here-but at

the turn of the 20th century, this square rose. That's a theater at the

end and this large square is a scene for outdoor concerts in the summer.

Above the elegant arcades rise these lovely windows with their delicate reliefs including the Venice lions at top ...

... and this not so lovely functioning clothesline reminding us that,

unlike Venice, this is a real town where 200,000 go about their daily

lives -- while 4.5 million tourists storm through.

Let's conclude with this. I usually don't take a lot of restroom

pictures, but this public facility offers separate prices based upon

whether you stand (20 cents) or sit (80 cents.) Men like it but the

women seem less enthused. Diocletian's once built an aqueduct to

this spot -- but for this?

Perhaps this is a best practice; but Split has a ways to go before its tourist infrastructure is commensurate with its Roman remains and economic importance to the Dalmatian coast. In 2006, only about 5% of the 4.5 million visitors here stayed overnight. Good places to stay are still hard to find even though the mayor is offering financial incentives to hotel builders.

And now for something completely different: Did you know that Split with a population of only 200,000 people has produced (as of 2006) 67 Olympic medal winners, not to mention 2 Wimbledon champions? At these prices, no one here sits down very often.

Thanks for viewing. If you're into Roman military history, you may

be interested in our discussion of one of the most significant forts of

Hadrian's wall. It's one of our most popular web pages and you can read

it by clicking here.

|

Please join us in the following slide show to give Split the viewing it deserves by clicking here. |

Geek and Legal StuffPlease allow JavaScript to enable word definitions. This page has been tested in Internet Explorer 8.0, Firefox 3.0, and Google Chrome 1.0. Created on February 9, 2010 |

|