Now let's take a walk west through

the heart of Úbeda. Let's start with a quiet

doorway whose historical significance is nearly smothered

by tree branches.

Enter the Renaissance here

The church of Gothic-Mudejar style

church of Santo Domingo rises above its elevated and

well-shaded courtyard. The tower we see here (below left) was added in

1702 by architect Francisco Caballero, much later than

the rest of this church. Remains of medieval churches

going back to the 13th and 14th centuries can be found

beneath Santo Domingo’s foundations.

Many churches in eastern Andalusia were named for this

saint who supposedly ransomed many captured Christians

from the Moors of Granada. Climbing the stairs, we found

Santo Domingo tucked into its own quiet pocket park that

nearly obscures some of its outstanding details -- Such

as this quiet door (below) through which Úbeda

walked into its Renaissance century.

The south door is from 1520-25, making it one of the

first Plateresque portals in then Gothic and Mudejar

Úbeda. How about those stacked columns? Note the

vegetable frieze at top -- there is very little religious

about this church door. The rest of the church has long

since gone over to the secular side as well, having been

used as a warehouse and is currently a workshop.

The picture above right shows a

detail of the rosettes that decorate these precisely cut

arch stones (called voussoirs). The cleric's hat

is that of Don Esteban Gabriel Merino, the bishop who

commissioned this doorway just as the Renaissance was

about to rebuild Úbeda in the 16th century.

Previous bishops were pretty staunch proponents of the

Gothic. The architect/mason was Diego de Alcaraz, a

local. (Andrés de Vandelvira, who was 11 years old

at the time, may have later mastered the Renaissance in

Úbeda, but Diego introduced it.) During the 5

years that this door is constructed, Francisco de los

Cobos will accompany the Emperor on their first trip to

Italy where Francisco will discover and bring back the

High Renaissance to his home town where this door has

already been added to a Gothic church. (Need some

historical context? About this time the pope is trying to

raise money to rebuild St. Peter’s in Rome by

selling indulgences and a young German priest named

Martin Luther is fussing with him about it.)

Enough of St. Peter’s in Rome; Let's now go to

Úbeda’s St. Peter's square, a mishmash of

buildings from the 13th through 19th centuries.

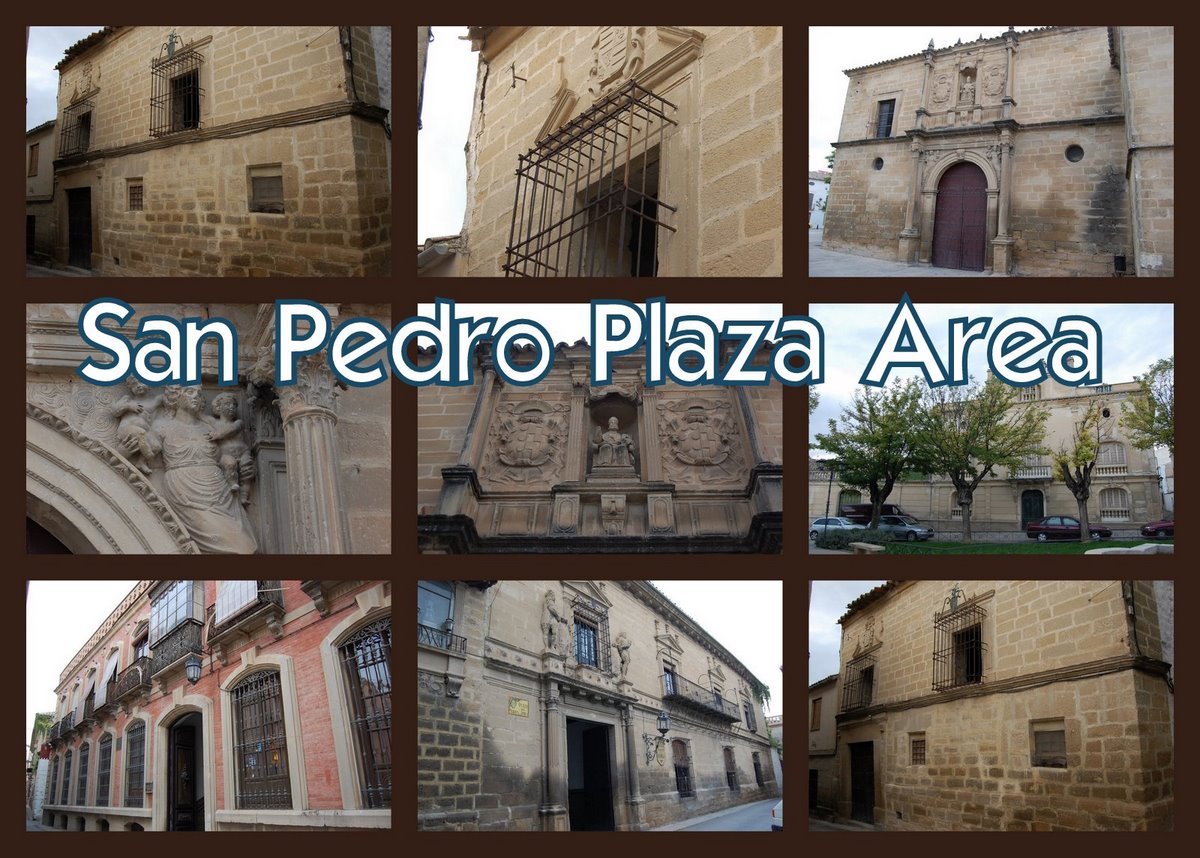

San Pedro Plaza

In the collage below, we see the

restoration of the palace of the counts of Guadiana.

Temporarily, it's a "see-through building." Like many

European restorations, the facade will be retained and a

modern building created within it. As a UNESCO world

heritage site since 2003, Úbeda requires its old

town facades to remain unchanged. Therefore this was (and

hopefully will return to being) an extraordinary

building. At right in the collage (thanks to Wikipedia)

we see an old picture of the palace: including caryatids

and, suggestive of Vandelvira’s Vela de los Cobos

palace, another set of stark white Doric columns on its

corners -- all capped by a large gallery.

Attached to the counts' palace is the simple church of

Saint Peter shown below. It's squarish shape suggests

that it may have been built over an Arab mosque.

Mostly Gothic, its Romanesque apse dates to the 2nd half

of the 13th century, shortly after the Christians took

back Úbeda. Its Plateresque doorway is obviously

much later. This facade was added in 1605 by Alonso

Barba, a follower of Vandelvira. Below right we see

a woman holding twins next to the Corinthian column. Set

amid Van Goghish swirls, she represents the virtue

Charity. (Faith is on the other side of the door holding

a cross and supposedly Hope was being reserved for

Obama.)

On either side of Saint Peter

(below), we have the crest of the bishop of Jaén

on whose watch this facade was added: Sancho

Dávila.

Los Orozco Palace

St. Peter's is a lovely square

with a bit of green. The entire south side is taken up by

the monolithic white wall of a Franciscan convent; but

the west side has the more recent (19th century) Los

Orozco Palace (below).

This is a French influenced building as seen by the bows

above the windows (as

seen in the picture below). Úbeda’s

most famous writer (after John of the Cross) is the

modern Spanish novelist Antonio Muñoz Molina who

set some of the scenes from his first novel in this

palace. (He now lives in New York City.)

Palaces to hotels

A walk through the narrow streets

reveals many lovely Renaissance buildings now often used

as hotels as is the case here with the elegantly

burglar-barred Hotel Ordonez Sandoval shown below:

Below we have the 16th century Rambla Palace with its

classical facade including these gentlemen at right

leaning on similar coats-of-arms.

Let's venture next to a more modern square that seems to

move traffic from the old town into the newer areas: the

Plaza de Andalucía. Join us by clicking

here.

Please join us in the following slide show to

give Úbeda the viewing it deserves by clicking here.

|

|

|

|

Geek and Legal Stuff

Please allow JavaScript to enable word

definitions.

This page has been tested in Internet

Explorer 7.0 and Firefox 3.0.

Created on 15 February 2009

|

|

TIP:

DoubleClick on any word to see its definition.

Warning: you may need to enable javascript or allow

blocked content (for this page only).

TIP:

Click on any picture to see it full size. PC

users, push F11 to see it even larger.

<