| You may prefer to see these pages as a photo slide show which contains the same text but presents the pictures full screen size. If so, click on the slides presentation at the right. |

The Chinati Foundation/La Fundacion Chinati displays the works of a few modern artists in a space integrated with the Chihuahuam desert which surrounds it in Marfa, Texas. Because of its distant and sometimes hostile location, few will visit these intriguing exhibitions. But you can through our Nikon's lens.

The minimal artist and uber-art critic Donald Judd stopped in Marfa once on his way to Baja -- and kept coming back. The Texas light and the remoteness from New York city were the two great attractions. Finally he scraped together funding to create a most unconventional museum -- one dedicated to showing the work of three artists in permanent exhibitions they helped design.

While Judd's vision may be compelling, it makes many Mohammads come to rather distant mountains -- and deprives huge audiences of seeing some rather intriguing work. During the peak tourist season, only a few dozen people per day stop by. The tour takes the whole day. This is one of the poorest and least populated areas of the country, averaging only two (often strange) people per square mile. Two major airports are each about a four hour drive away.

But Chinati redeems itself by encouraging photography of the works -- unlike most museums. While photography does not serve sculpture all that well, it's all we've got unless you make the trip here.

Judd converted a deteriorating army camp into one of the world's most unconventional museums. The site exploits 1) the original unmodified camp buildings (above left), 2) modified buildings to control the natural light as seen with the Quonset-like hut (center), and 3) the high Chihuahuan desert landscape as symbolized by the mesa rising at right.

Judd insisted that modern sculpture be displayed permanently in an environment the sculptors, not museum curators, controlled. His essays touted such displays as the standard for future exhibitions. Originally the Chinati Foundation (named after the nearby mountain chain) was to display the works of Judd and two of his friends: the minimalist Dan Flavin and the Abstract Expressionist John Chamberlain.

Above we see a case in point: this was one of two artillery sheds for the old Fort D.A. Russell. Judd (an architect of sorts) added the semi-round corrugated galvanized roof to improve the looks of the building. Mundane garage doors were replaced by huge windows, the better to encourage Texas's blazing sun to splash over the 100 untitled sculptures that Judd would create inside.

Here's a side view of the same shed showing the boxy sculptures inside -- and the rough terrain of the exterior. Our two-day visit started on April's Fools Day 2010- as good a time as any to let these minimalists and the desert spring have their way with us.

This is one of at least four spaces at the Chinati Foundation dedicated to Judd's sculpture. Nearby (and far away in New York City), the Judd Foundation shows more.

Judd's work is captured in four main displays on this old base: permanent displays of boxes (inside and out); a temporary exhibition of his wall hangings (more boxes); and a former gym empty save for his furniture (which is, of course, pretty boxish). Let's start here with these shiny boxes which blur the line between their surface and their surroundings.

The two artillery sheds hold 100 identically sized aluminum boxes conceptualized by Judd specifically for this space.

These buildings originally had sides filled with garage doors like modern loading docks or storage units. This allowed easy access during WWII to the chemical mortars and ammunition. These powerful weapons could hurl shells over two miles with precision of about 50 yards. Their name derives from the fact that they could fire both white phosphorus (to block the enemy's view) and mustard gas (which was never used, leaving the US with a huge chemical weapon stockpile at the end of the war.)

These two sheds occupy the edge of the 340 acre museum site and roughly parallel US 67 which runs 1600 miles from Iowa to the Mexican border. Perhaps by coincidence, the artillery shed axis is nearly perpendicular to the path of the sun in this part of Texas. But perhaps not: the many U-shaped barracks which housed the troops are laid out in an arch at left which would minimize the sunlight which hits the cot area.

Here we stand outside looking through one of the artillery sheds and at the aluminum box sculptures inside -- and the cement box sculptures in the field beyond. More on them later.

The Chihuahuan desert floor can experience high temperature of up to 160 degrees Fahrenheit (71 Celsius) in the summer. These buildings are not only naturally lit, but seem to lack air conditioning as well. (Their roofs sport vents, however.) Job security for the foundation's conservationists!

Inside, the sun interacts with sculpture and people. Often I would take a picture, examine it in my small camera display, and find that the aluminum box had all but disappeared into a splash of sunlight.

The two sheds contain exactly 100 of these milled boxes -- all with identical exterior dimensions and none of them with common interiors. Sometimes they reflect, sometimes they are transparent, sometimes both.

Before his minimalist art produce maximal profit, Judd supported himself as an art critic and reviewer. He viewed the Chinati Foundation as being the standard to calibrate the display of art. He wrote in the catalog: "It takes a great deal of time and thought to install work carefully. This should not always be thrown away. Most art is fragile and some should be placed and never moved again. Somewhere a portion of contemporary art has to exist as an example of what the art and its context were meant to be. Somewhere, just as the platinum iridium meter guarantees the tape measure, a strict measure must exist for the art of this time and place."

The 100 untitled sculptures each are 41 X 51 inches by 6 feet wide. Every outside is the same, every inside is different.

Picasso meets Judd: Here a photographer both captures and creates the scene, reflected in the boxes and back again, her body image fractured and spread -- and giving new meaning to Cubism.

These works were created from 1982 through 1986 and were designed with geometrical partitioning of the space in the two sheds. Judd often used math to help design his sculptures.

On the rear wall is a sign in German probably meant to inspire the prisoners-of-war held at this camp.

Here's a detail of the construction of these milled aluminum boxes fabricated by the Lippincott Company in Connecticut.

Judd's sculpture was pretty much all about boxes. While he abhorred the term minimalism, as a critic he defined the movement and its emphasis on the experiencing of the physical object rather than the representation of some other object or idea.

Judd moved here in 1981 after tiring of the New York art scene.

The semi-circular ends of the building are corrugated steel but were intended by Judd to be made of glass. From the outside, the building now appears twice as tall and has an army base feel to it. Inside, the function is unchanged as no new internal volume was created.

Through an original window, we view the next shed.

What is real, and what is Memorex?

Same box as before without the people or sunlight!

While the exterior has a "Quonset hut" roof added by Judd for aesthetic reasons, the interior keeps many of the rough touches of the original artillery shed as we see here in the concrete ceiling.

The buildings are laid out on a northeast-southwest axis so the morning and afternoon sun in this part of the world hits the structure nearly broadside -- and changes the boxes accordingly.

At 10:30 in the morning, the west windows are placid.

The Chinati Foundation got started with a grant from one of those de Menils who have benefited Houston's art world so well. The funding structure was the DIA foundation.

Jane in a moment of reflection

The Dia Foundation was started by a daughter and son-in-law of Houstonian Dominique de Menil. The Dia foundation likes to support art projects which are unlikely to happen otherwise due to their scale.

These boxes float into each other, disappear, and serve as table tops for the mesas on the horizon.

But Dia support of Chinati had a troubled beginning. From 1980 through 1986, Dia gave Judd US$ 4 million to start the Marfa project, then withheld further support because of financial problems. Judd was by then a Texan and, of course, threatened to sue for the rest. This led to the establishment of the Chinati Foundation -- and continued Dia support.

Judd died in 1994 at age 65. He started as an expressionist but became enamored of industrial materials and was one of the first artists to design and allow others to fabricate (unless we consider that this is what happened with the great artist studios of the Renaissance and before.) Once again, art was a collaborative affair. Judd's collaborators also include the sun, the Texas high desert, and the viewers of his work. (And if that statement is no fabrication, then this art can't be captured in photographs. Zeno's paradox, anyone?)

The original shed had garage doors -- now replaced by Judd's massive windows. Through these windows, we see our next Judd sculpture set in the background, the cement boxes.

Google maps show 13 of the 15 concrete (literally) sculptures of Judd at the edge of the 350 acre property. While the old army base forms a segment of a large circle, Judd placed his boxes on a rigid north-south axis -- which coincides exactly with the 104th degree of longitude and measures exactly one kilometer in length. We told you he likes math!

As Pat Robertson would say "True story": when I first saw these, my knowledge of minimalism was quite minimal. I asked our guide (a foundation intern) if these were pill boxes from the days of the army fort -- but only because I couldn't imagine such a large sewer being installed in this dry desert. She didn't seem too shocked by my question, as if she gets it from Philistine visitors all the time. (Or maybe she thought it was my own lame April's fool joke.)

A thoughtful essay claims that one of these sculptures was struck by lightning. Our guide said that all of them had been freshly restored. Given 35 mph gusts of wind, we chose to photograph these from a distance.

A small museum building displays the drawing Judd used to design the boxes (both the aluminum mill internal boxes and the external concrete ones.)

By dividing his kilometer-long space, Judd determined that each sculpture set would be 60 meters (measured center-to-center) from each other. (My calculator puts them at 66.6 meters apart. Go figure.)

The 15 sculpture sets have 60 boxes in total -- each of them 2.5 X 2.5 meters and 5 meters long. (The entire world knows what that means except for those of you who live in Burma, Liberia, and the United States who think of it as about 8 feet X 8 feet by 17 feet.)

Unlike the 100 aluminum mill boxes inside the artillery sheds, these boxes have four external variations: one short side open, both short sides open, one long side open, both long sides open. This allows the interiors to capture different amounts of light as the sun passes over them.

The first two concrete boxes were installed in 1980 and the last four in 1984. They were here before most of their shiny inside cousins.

The kilometer-long site is about the only available flat portion of the property in these foothills.

And now for something completely different...

...Well, sort of different. It's the same in that this is a Judd sculpture and so it's going to be all about boxes. Like the concrete boxes atop the 104th parallel, these boxes project from a long spine -- and have a mathematical basis. Unlike those boxes, this is a temporary exhibition.

This third set of Judd boxes is lit, of course, by natural light.

These sculptures have a mathematical basis: From the right to left, each galvanized box is doubled. From left to right, each space between is doubled. Others here use natural numbers. Others by Judd (not displayed here) use Fibonacci sequences like those that inspired the Pythagoreans and the Greek architects with their golden rectangles.

Close-ups provide a different view...

...including a bit of kaleidoscope that Dan Flavin might have liked.

Above is a piece of work used to thinking inside the box. The box at upper right peers into his soul.

Did Mondrian predict minimalism?

This temporary exhibition uses a barracks, like the Flavin permanent displays. However, this one uses side windows as well. All light is still natural, of course.

Our final Judd exhibit is his minimalist furniture displayed in the old fort gymnasium, now called "The Arena."

The "arena" started life in 1914 as a hangar and in WWII served as the base gym. After that war, Fort Russell was given to the Texas National Guard and eventually most of the land was parceled up and sold to local citizens.With the Dia foundation, Judd purchased the buildings and 340 acres of land in the late 1970s.

On the way to the Arena, we passed over this mini-Stonehenge. It's called "Sea Lava Circles" and is a 1988 work by Richard Long who collected this volcanic rock in Iceland. (Rocks to Newcastle? The nearby Chinati mountains were made by volcanoes, so there's little need to import such rock.) Each stone just touches the next and the outer circle is almost 14 feet in diameter. Judd put it on the old tennis court.

It's one of two sculptures with an Icelandic connection here in this hot desert.

Inside, the Arena is sparse -- the better to appreciate the Judd furniture. The hardwood floor has been given over to gravel punctuated by long concrete strips that kept the hardwood from sinking into the desert. When the fort was abandoned after WWII, the wood in the floor was re-purposed and replaced by sand. This made sense as the basketball players were replaced by horses, hence the name "arena."When Judd restored the space, he intended for it to have one of his long sculptures.

Here we were allowed to touch Judd's work. In fact, you can buy this furniture on the open market or from the Judd foundation. Here we see Dick thinking inside the box.

Judd created cement floors at each end of the space. The walls up to the high windows are of adobe but the roof is held up by a 66' truss which Judd wrote was pretty good for 1914 construction. Before it was a gym, this served as a hangar for the biplanes that patrolled the border and tried to keep Pancho Villa at bay. While we were here, winds gusted to 35 mph -- probably enough to keep a fragile bi-plane indoors.

I loved these doors! They only get opened a few times a day, but when they do, a crowd streams in. These pivot on a central axis and turn to let folks in and out on both sides. Like all of the best Judd stuff, it's basic, clean, and elegant in its simplicity.

Another view of the door, looking out at the gate. Boxes rule! The doors at the end of this pathway are freestanding.

Here's a bed for two with a bundling board sufficient even for Puritans (or perhaps rowdy siblings.) It's high enough so each gets his own privacy.

Rather than rip up the old foundation, Judd adapted it to a patio.Here Judd's minimalist chairs become benches with the addition of a single plank. His furniture continues to be on sale. Plywood chairs like these run about US$ 2000. If that's not enough, the Judd Foundation hopes to raise US$ 20 Million next month in an auction.

We found rosemary common in Marfa as a decorative shrub. Typically it grows much larger here than what we typically see in Houston -- and throughout the high desert we saw it blooming which we never remember happening in Houston.

A view from the Arena patio over Richard Long's sculpture and towards Ilya Kabakov's School No. 6.

The second of the three artists who anchored the Chinati Foundation was Dan Flavin, master of the fluorescent light.

The old army barracks were U-shaped buildings with rows of cots on the two long arms and an assembly area at the bottom of the U. Six of these buildings have been dedicated to the light sculptures of Dan Flavin.

These barracks are the only galleries that were NOT completely naturally lit. At the end of the long halls, two windows admit the light. Given the orientation of the buildings, this would be very intense light in the morning.

Here we look down at the bottom of the "U" at center. The two windows on each side are the only openings inside. Often the courtyard has a fruit tree which in the desert Spring could steal the show from the art inside. Note the dormers on the roof. We didn't see much sign of air conditioning here in a town where summer highs average over 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

Here's a typical side view showing all of the windows boarded up.

This provides a stark interior space lit only by sunlight that in the morning would stream through the two windows at the bottom of each leg of the "U" barracks. Here the afternoon sun provides a softer glow.

Another courtyard view showing the boarded up windows.

The stark white walls prepare the viewer for the gentle pastel tones emanating from the bottom of the "U" from twisted parallel rooms ...

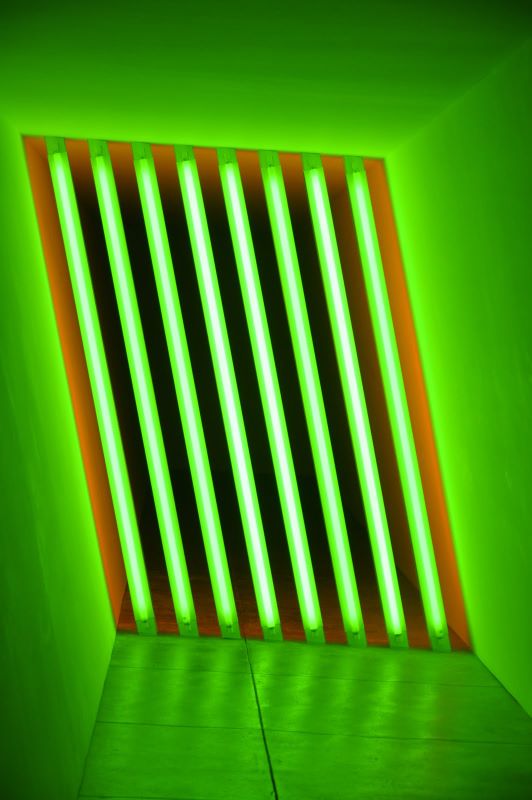

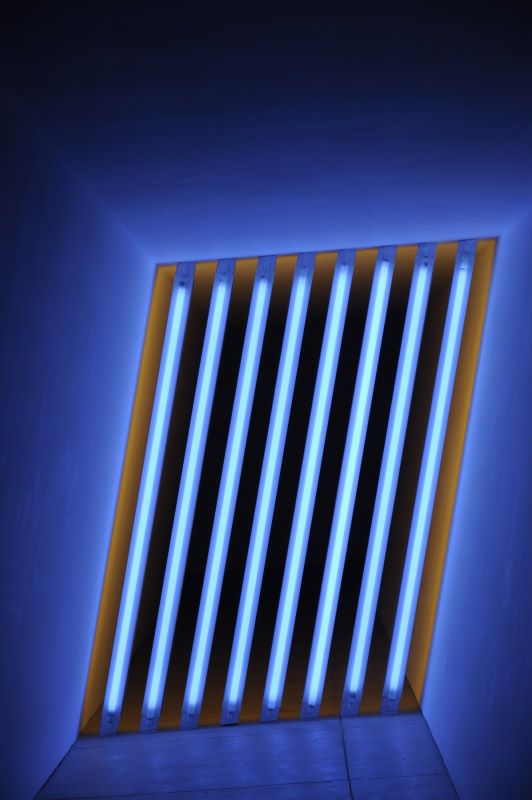

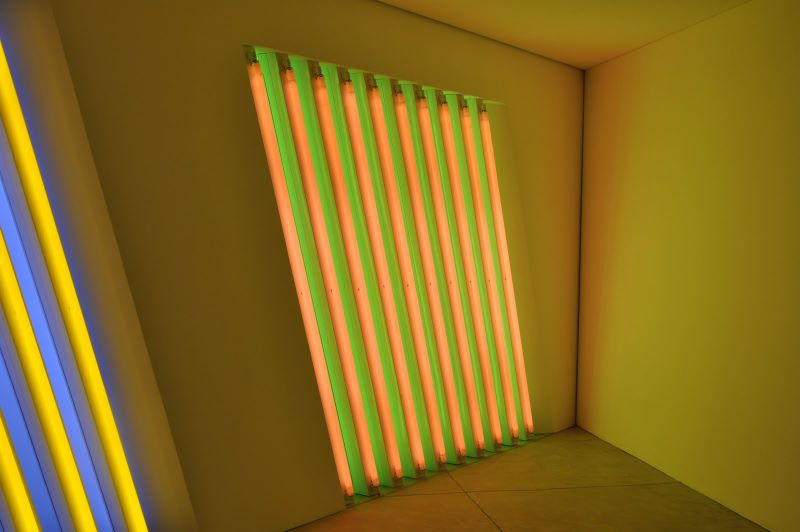

...and leading to the Flavin sculptures made from then off-the-shelf fluorescent tubes 8 feet in length and in various colors no longer manufactured.

Flavin's work occupies six of the old military barracks and each is the same: very long stark white spaces that culminate in two of these colored fluorescent light sculptures.

The viewer enters a perfectly rectangular space through the long barrack arms that once held soldiers' cots. At the bottom of the "U," they are greeted by glowing tilted spaces of colored light.

A gallery owner who was selling Flavin prints told us that Flavin said when the bulbs burnt out, the art was over. Conservationists are not about to let that happen. They have extra bulbs in stock, as does the Flavin foundation. Burnt out bulbs are replaced by ones slightly used; new ones would glow too brightly. When Flavin did this work, these bulbs were off-the-shelf items.

If Flavin did make that statement, then is the art over when the people go home and the museum staff turns off the power? If a fluorescent bulb glows in the forest, and nobody sees it, is it art?

Flavin was no stranger to our Houston de Menils, of course. Dominique de Menil had him conceptualize a permanent installation starting in 1990. He completed the design two days before his death in 1996 and his studio implemented it in Richmond Hall, an old grocery store two miles from our house that's now part of the Menil Collection. Here we do not live by bread alone.It was not only Flavin's last commission, but Dominique's as well. She died the next year.

Like our Houston Flavin dedicated space, this gallery was also implemented by Flavin's studio after his death.

The six buildings have the sculptors presented at the bottom of their "U." Typically these are housed in long tilted corridors -- two sculptures at each end.

The lights are spaced far enough apart to see fellow Houstonians, should they be on the other side.

Flavin had a 35-year love affair with light, starting in 1961. In 1963, at the age of 30, he began to work exclusively with off-the-shelf fluorescent tubes.

Here we see the two parallel corridors that occupy the ends of 5 of the 6 barracks used in the Flavin exhibition.

Most of his work is untitled -- but dedicated to fellow artists, especially to Russian sculptor/painter/architect/musician Vladmir Tatlin. From Tatlin, he picked up the technique of putting his art in a corner where it would interact with several sides of the room. Most of his "Tatlin" dedications are stark cool white fluorescent including several displayed in the Houston Menil space.

While I couldn't find a way to get a church interior into this set of slides, one of Flavin's last works was a church interior in Milan, Italy. Often in religious painting, light streams denote the presence of God.(Flavin spent 5 years in a seminary but was never ordained. His studio was made from a converted church in Bridgehampton, NY -- now run by the Dia foundation.) If you are interested, check out the church by clicking here.

Two of the few Flavin sculptures not hidden in a double tilted corridor

Outside the Flavin barracks, the trees were bursting with the Texas spring...

...and inside at the end of each barrack arm, we have two Wyeth windows framing the Chihuahuan desert.

It's not that easy being green.

2010_04_01_chinati_foundation_dan_flavin_90.jpg

2010_04_01_chinati_foundation_dan_flavin_97.jpg

Sometimes Flavin made light of us.

The Chinati Foundation's John Chamberlain building occupies an old factory along the railroad tracks in downtown Marfa, about a 5 minute drive from the old Fort Russell.

Donald Judd bought up several buildings in Marfa and turned them into studios, exhibition space, and architect offices. When you see a fence such as this....

...it means that it is "branding" a Judd Foundation or Chianti Foundation space. The mortar projects outward about an inch from the bricks. Here the fence surrounds the large Chamberlain building.

But the fence also brings together the various smaller buildings incorporated into the Judd empire. Judd also purchased several farms and owned nearly 40,000 acres of Texas desert at one time. (Probably enough to support 4 or 5 cows.)

Inside, Chamberlain's work spreads out inside an old textile factory which processed wool from the sheep who could scratch their nourishment from the local desert hills.

Inside, 23 or so of Chamberlain's smashed auto parts sculptures occupy the space of what was once a wool factory.

Chrome and industrial paint emblazon this space converted by Judd and Chamberlain.

Rivets and welds hold these structures together.

Again, natural light is the sole source of illumination. Given the size of the space, skylights are sometimes used. This Chamberlain work is on loan from Houston's Menil Collection. We are in no hurry to get it back.

Ten of the sculptures are named after Texas sites and were fashioned (assembled?) in Amarillo -- home of the ten buried Cadillacs which seem to have nothing to do with this exhibition. We may have buried the wrong stuff.

OK, for those of you who like Chamberlain's stuff, I apologize.

It's not obvious why the king of boxes (Judd) would be pals with the king of chaos (Chamberlain).

Chamberlain always gave as his reason for using auto fenders that it was free. His first victim was a 1929 Ford which became a piece called "Shortstop."

This went on for nearly 60 years. While we see only fenders here, Chamberlain also used paper bags, toy trucks, and aluminum foil.

Here a diffuse skylight helps illuminate the center of this large space.

When describing his art, Chamberlain has said that 1) it means nothing and 2) "It's not a product, it's information." That helps.

In the middle of the floor, we see a sandbox. Just when we thought the sculpture was abstract expressionist, it becomes minimalist. Or maybe they have a kid -- or cat.

Besides the wrecked cars, the entrance sports this large couch that eats people while they watch a video made by Chamberlain.

The Chinati Foundation hosts about six artists a year in an artist-in-residence program.

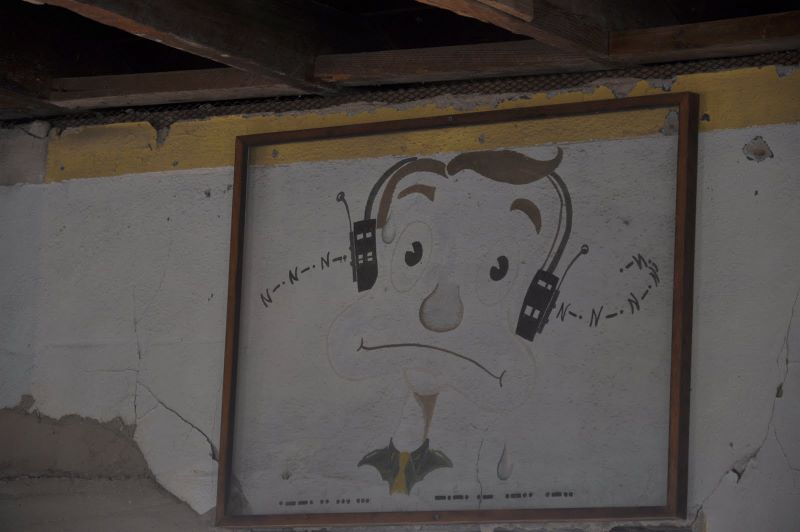

The first artist-in-residence long preceded Donald Judd to Marfa. These were the anonymous and bored souls who decorated their mess halls. At right we see some of the horse maintenance equipment left over from cavalry days and displayed here.

The mess halls run perpendicular to the barracks. Most are now used to display other artists' works, but Judd liked the paintings on this one and preserved them.

Here's another view of the contraptions that have something to do with holding a horse still while he gets his maintenance. Don't ask -- or give ideas to Dick Cheney.

A boarded-up door becomes a bit of found art.

Judd had these frames installed to provide a bit of protection for the wall mosaics which are otherwise exposed to the harsh climate. (On a single day in April, we found a variation in Marfa temperature from 24 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit.)

Before the iPod: we found Marfa with its own quirky NPR affiliate.

Longhorn fans were around even then.

And something for the dogs. An old Texas saying is that it's so hot that the trees are bribing the dogs. Typically we found this area so dry that trees were rare indeed. Truth be told: hydrants were even rarer. One local who served his volunteer fire department for years says because of the remoteness of homes and the lack of water, they rarely save a burning house. Their motto is, "We've never lost a slab."

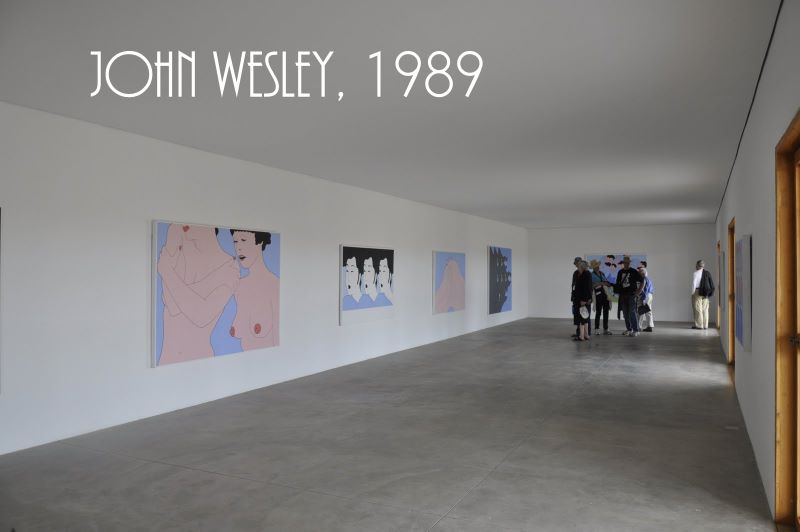

The first artist-in-residence was John Wesley who lived here in 1989. A considerably rehabilitated mess hall has been given over to displaying his paintings.

Pop artist Wesley was in his early 60s during his residency here. Although representational, his pals were the minimalists Flavin and Judd.

As an art critic, Judd praised Wesley early in his career as an up-and-comer.

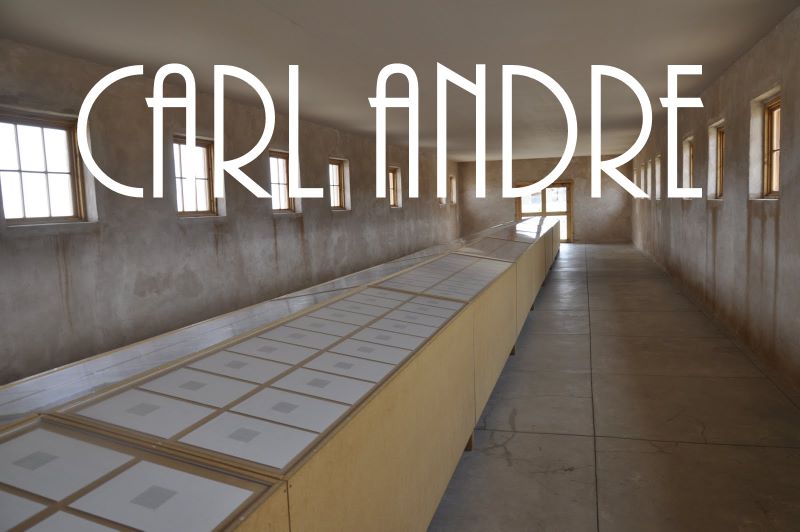

Another mess hall displays the "paper sculpture" of Carl Andre. Andre once channeled Caravaggio but was acquitted for murdering his fellow artist and wife. He is known mostly as a sculptor of monumental public art. But here we see quite a different side...

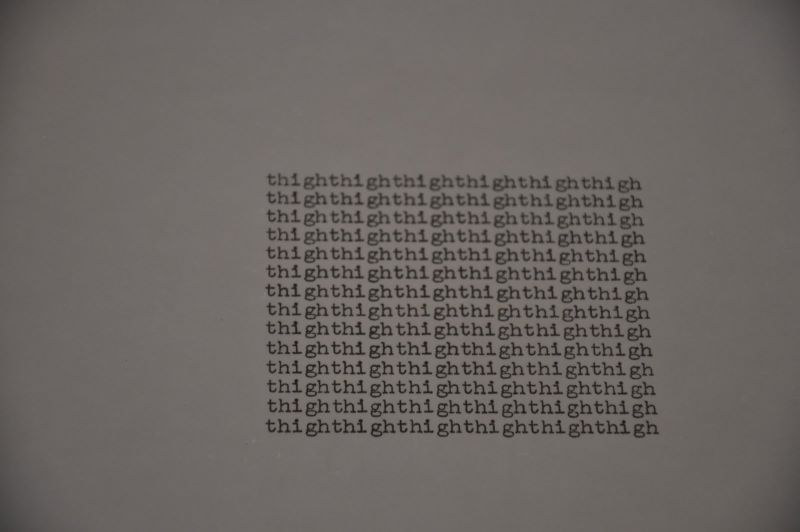

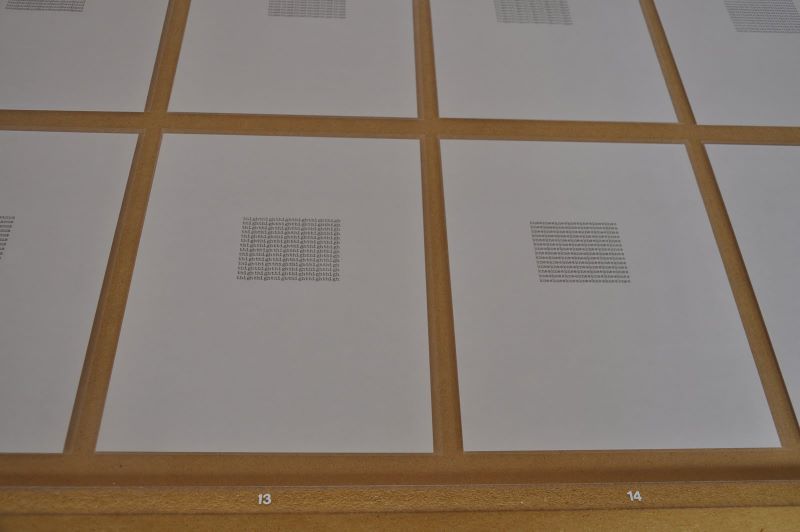

...these are his "poems." From 1960 through 1964, he sculpted little but wrote these visuals on a typewriter...

...look closely and you will see the same word typed many times. At left we have the thigh, at right the knee. Andre pretty much moves through the body like the song "Dry Bones."

These poems (or drawings) range from 1958 through 1972 and were donated by Andre to the foundation.

With Judd and Flavin, Carl Andre helped define minimalism. Here he designed the glass cases himself. Did he intend the viewer's body parts to be reflected while they read his minimalist poems about body parts?

Another mess hall features two copper cylinders by Roni Horn, an American with a huge fetish for Iceland.

Only four visitors at a time were allowed into this mess hall; the reason given was that these were very delicate works.

Judd had many artist friends. Two of his New York buddies, Claes Oldenburg and his wife and collaborator Coosje van Bruggen, visited the foundation in 1987 and were inspired by the grave of "Louie" -- the oldest horse in the cavalry when it was disbanded. All the army's horses and all the army's men went elsewhere, but Louie stayed. The two sculptors created this aluminum and polyurethane foam work in 1991.

Fort Russell started life as a cavalry camp a century ago when Pancho Villa's revolution in Mexico threatened the Texas borderlands. It grew during WWI but was abandoned during the depression. WWII saw it redeployed to house WACs, chemical mortar battalions (they could fire mustard gas -- but didn't), and German prisoners-of-war.

The stone above marks the grave of the last horse in the cavalry: Louie. This base inspired the Oldenburgs to copy it for their horseshoe. Every large American town has an Oldenburg including Houston's library mouse. Now tiny Marfa does too.

TOP GUN? At its peak, the cavalry here housed 400 horses or mules. But this spot's quirky place in history is probably as an air base. During the Mexican revolution, biplanes from here surveyed the border and supposedly the first dog fight was two American contractors (one working for the US and the other for Mexico) shooting pistols at each other from biplanes.

Oldenburg nailed this one. The 400 steeds were accompanied by 650 soldiers -- and contributed about a half million dollars to the Marfa economy, helping the town survive the depression. Eventually the fort, once called Camp Albert, took the name of the Union General and Civil War hero David Allen Russell. Like Judd, Oldenburg, and Van Bruggen, he was a New Yorker.

Eventually the army closed down the fort -- but Marfa citizens donated 2400 acres so it could be reopened in 1935 as a training installation.Oldenburg and van Bruggen collaborated on more than 40 monumental public sculptures before her death last year ended their 30+ year marriage. The equestrian sculpture of "Louie" may be their least seen public work.

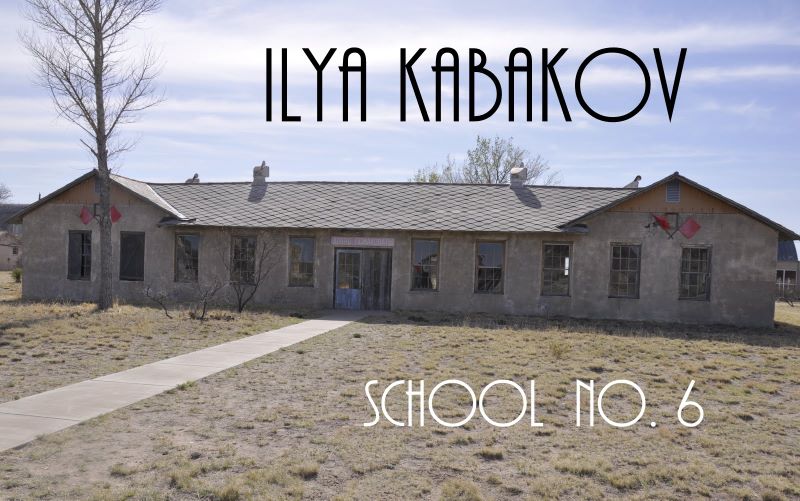

Here we see an entire building that is to be treated as an integrated sculpture or "installation." It's by Ilya Kabakov who once made his living in the Soviet Union by illustrating children's books. Eventually he moved to Long Island but, in 2008, relocated to Moscow.With this 1993 gift to the foundation, he returns to his artistic roots, creating an abandoned Soviet Union era elementary school.

The sculpture/building depicts an abandoned Soviet elementary school which no longer indoctrinates children with the country's political and social values. (In Texas, our school board calls that "education.") The overall feeling both inside and out is one of decay and failure. This includes even the courtyard which seems to be losing its battle for respectability against the Chihuahuan desert.

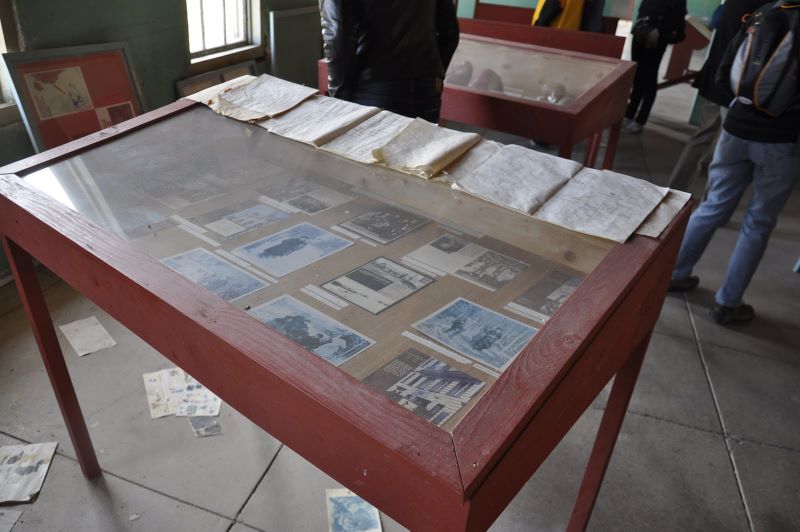

Inside, where Kabakov could control the space, he has strewn the detritus of early education throughout the old barracks which he has lightly partitioned.

During Soviet years, Kabakov carefully navigated between the benefits of being an "official" artist and his private life where he created his own work. After the Soviet Union fell, he began to collaborate with his niece Emilia -- and not just in art. They eventually married.

A "propaganda" display. Portraits of Lenin still cling to the walls.

Abandoned school desks and book cases move the eye to poignant musical instruments.

Look closely: the floor is littered with paper. We were told to watch our step. How will future conservationists conserve artistic trash?

Named one of the ten greatest living artists in 2000 by ARTNEWS, Kabakov here practices conceptual art where the idea is all important and such things as aesthetics, materials, and even execution are secondary.

|

Please join us in the following slide show to give the Chinati Foundation the viewing it deserves by clicking here. |

Geek and Legal StuffPlease allow JavaScript to enable word definitions. This page has been tested in Internet Explorer 8.0, Firefox 3.0, and Google Chrome 1.0. Created on April 16, 2010 |

|